On Air Now

The Classic FM Hall of Fame Hour 9am - 10am

24 August 2017, 16:50

Life not going according to plan? WORRY NOT. Some of the world's greatest composers bounced back from almighty failures. Here are some of the most inspiring stories from musical history.

Jean Sibelius

Throughout his teens, Finnish composer Jean Sibelius had his heart set on a career as a violin virtuoso. After graduating from the Helsinki Music Institute he took himself off to Germany, and then Austria, where he auditioned for a job in the renowned Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra.

They turned him down.

Sibelius headed home, saying ruefully “it was a very painful awakening when I had to admit that I had begun my training for this exacting career too late.”

But, to misquote a well-known saying, “If at first you don’t succeed – try something else!”

Sibelius decided to concentrate on writing music instead of playing it, became his country’s best-known composer (the Helsinki Music Institute is now called the Sibelius Academy) and wrote one of the greatest of all violin concertos.

The Vienna Phil’s loss turned out to be music’s gain!

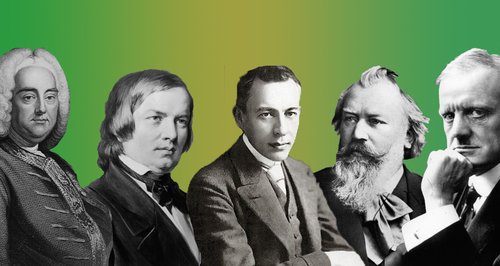

Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann was another budding virtuoso, who was determined to become a great pianist. That’s a big commitment – and he also had to go against the wishes of his parents, who wanted him to become a lawyer.

He practised and practised, and there’s a story, still disputed, that he made some sort of mechanical contraption to strengthen the little finger of his right hand. Sadly, either this device, or overwork, had the opposite effect, and he ended up with a permanently damaged hand.

But, like Sibelius, Schumann didn’t give up – he too decided to concentrate on composing. And then he fell deeply in love with his piano teacher’s daughter Clara, one of the greatest pianists of her time. Schumann turned his back on the madly difficult repertoire that had caused him to over-practise, and wrote the most Romantic, lyrical music for Clara to play.

George Frideric Handel

George Frideric Handel collapsed at his London home in 1737 with what was probably a stroke, and his doctor said: “He will never work again – we may be able to save the man, but we have lost the musician.”

No, they hadn’t – Handel stubbornly ignored medical advice and literally dragged himself back to work, although it wore him out. Until…

He read a new epic poem called Messiah and immediately he was filled with renewed energy! His manservant reported that when he went to wake him, “He got up! He ate half a Yorkshire ham in no time at all, and I’ve had to pour him four pints of beer!”

The old Handel was back, and he had just finished composing Messiah, which became his most famous work. When his doctor paid him a visit, Handel played him the whole oratorio. Hallelujah!

Sergei Rachmaninov

Classical music is unfortunately filled with cruelties. And no-one felt them more keenly than Rachmaninov: the initial failure of his First Symphony in 1897 haunted him for the rest of his life.

Rachmaninov wasn’t very confident about the work, and sadly, his worst fears came true: at the premiere, the fatal blend of an under-rehearsed orchestra and a drunken conductor - composer Glazunov, no less - brought about a fiasco that fellow composer and critic César Cui compared to the 10 plagues of Egypt. He added that the piece was fit only for a music conservatory in hell.

Rachmaninov called it “the most agonising hour of my life” – he hid in a stairwell, hands over his ears. His dreams, his hopes and confidence were destroyed and for the next three years he could hardly write anything.

After plunging into depression, he even locked the manuscript for his Symphony No.1 away in a desk. Eventually, with psychiatric help, he returned to work and his later Piano Concerto No. 2 proved to be a huge success, currently sitting at No. 2 in our Classic FM Hall of Fame.

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms was very close to his mother, and was desolate when she died – but there’s consolation in every bar of the Requiem he wrote while his grief was still raw, especially in the fifth movement when the soprano sings “Now you have sorrow, but I will see you again and your heart will rejoice…”