How did music notation begin?

7 August 2024, 13:03 | Updated: 8 August 2024, 09:51

Crotchets, quavers and staves are the product of centuries of evolution and refinement. But who started it all – and how different did music look a couple of thousand years ago?

Listen to this article

Whether it’s collective singing to enhance mood and feelings of social inclusion, or crafting musical instruments for ceremonial and military use, musical rituals have existed since the dawn of time. Some of the oldest instruments that still survive today are 50,000-year-old flutes, carved from bones.

We’ve been playing and listening to music for millennia – but when did we start writing it down?

It all started with the Ancient Greeks.

There are very few surviving examples of written music from Ancient Greece. But we do know that the Greeks were crucial in setting the groundwork for music theory.

Pythagoras, who lived from around 570 to 500 BC, was among the Greek theorists to explore the mathematics of music.

Together, Pythagoras and his disciples articulated for the first time the ‘Perfect’ intervals of the octave, fifth, fourth and second, pioneering the concept of a musical interval which is so embedded in our musical language today.

The Greeks also invented the tetrachord, which describes a series of four notes within a scale.

Read more: QUIZ – Could you pass Grade 1 music theory?

1,000 years later, their interest spread to Western Europe.

In the sixth century, Boethius, a Roman senator, wrote the influential De Institutione Musica (The Principles of Music), bringing the Pythagorian understanding of maths and music to medieval Western Europe.

A few decades later Pope Gregory – the man credited with invented the Gregorian chant – started the first music school in Europe: the Schola Cantorum. By this time, it was becoming quite fashionable to learn about music. Melodies were often learned and passed on by ear, as there was not yet any formal way to write a tune down.

This called for an updated system of music notation.

“Unless sounds are held by the memory of man, they perish, because they cannot be written down,” said the scholar St Isidore of Seville, who grew tired of forgetting music all the time.

In 650 AD, St Isidore developed a new system of writing music, using a notation called ‘neumes’. Vocal chants, which were the popular music of the time, would be written on parchment with the text, above which neumes would be notated, indicating the contour of the melody.

Read more: The medieval ‘Shame Flute’ was used to punish bad musicians in the Middle Ages

350 years later, Guido D’Arezzo introduced a new system.

Around 1,000 AD, Italian music theorist Guido D’Arezzo saw that people were struggling to learn chants from ‘neumes’ and thought there must be a more accurate notation system out there.

He created a system of four-lined staves (an early version of the five-lined ones we use today), and organised pitches into groups called ‘hexachords’. He also added time signatures and invented solfege – the framework we know today as ‘do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do’.

But music notation was still missing one thing: the duration of notes.

Around 1250, Franco of Cologne invented a system of symbols for different note durations, consisting mostly of square or diamond-shaped black noteheads with no stems.

In 1320, Philippe de Vitry built on his idea, creating a system of mensural time signatures for minims, crotchets and semiquavers. By 1450, white notes had begun to overtake black notation, so most note values were written with white noteheads – as you would write a semibreve or minim.

Then in the 17th century, note values started to look a bit rounder.

Throughout the 1600s, music notation continued to evolve according to the music of Renaissance and Baroque composers. And when instrumental music overtook vocal music as the most popular genre, a change in notation was needed.

Instrumentalists were still using Guido D’Arezzo’s system of staves and notation, albeit a slightly modernised version. But they found there still wasn’t enough direction within the notated music.

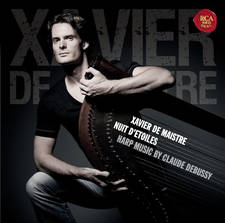

So, composers began to introduce bar lines and performance directions, including for dynamics, tempo and mood. Like this one...

Is music notation still evolving?

The 1950s saw the invention of graphic scores, which combine art and music in a sort of musical map, giving the performer a guide, rather than strict instructions, on how to play the music. As such, graphic scores are often interpreted as a reaction against the highly detailed sheet music of the 20th century and 21st century.

So, what will sheet music look like in the year 3,000? It could go completely back to basics again, and leave it all up to the performer to interpret the music as they wish.

Or it could get even more artistic, like this…