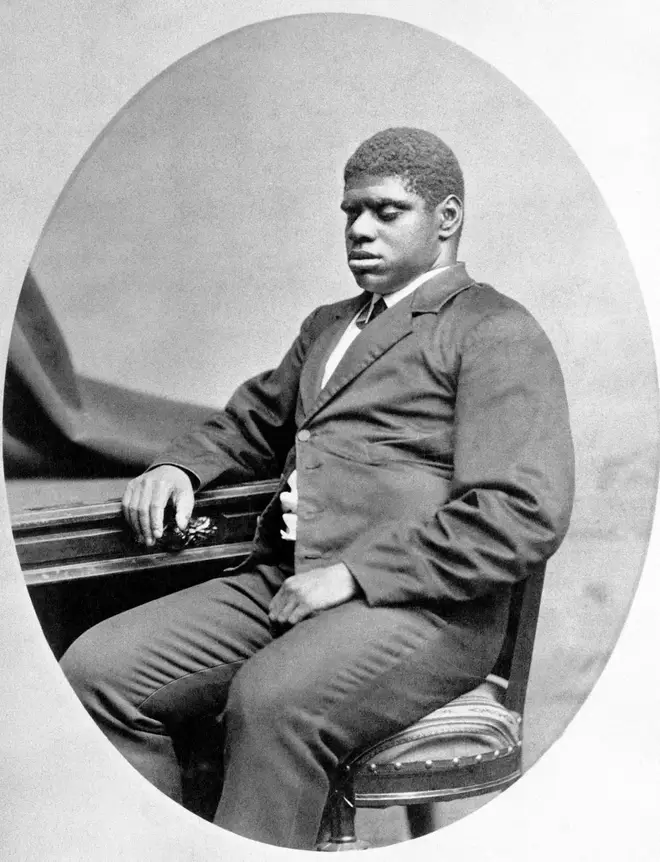

The story of Thomas ‘Blind Tom’ Wiggins, a 19th-century piano prodigy born into slavery

4 August 2023, 16:36 | Updated: 4 August 2023, 17:01

Thomas ‘Blind Tom’ Wiggins, who became the first African-American to perform at the White House, had his talents taken advantage of from an early age.

Listen to this article

American composer and pianist Thomas Wiggins (born Thomas Greene) was born in 1849 on the Wiley Edward Jones Plantation in Harris County, Georgia, America.

Shortly after his birth, Wiggins, who was blind and had undiagnosed autism, was sold along with the rest of his family at a discount price due to a new owner, lawyer, General James Neil Bethune.

As Wiggins was blind, he could not perform work which was demanded from slaves at the time, so instead he was left to explore his new plantation home. He became fascinated with sounds, such as the singing of a bird, or the rain landing on the tin roof, which he would lie under.

Wiggins soon began sneaking into Bethune’s house, where they had a piano which the General’s daughters would learn on, and tried to mimic the sounds that he had heard outside on the instrument.

He reportedly composed his first piece, The Rainstorm, on that piano when he was just five years old, inspired by the rain on his roof.

Read more: 19 Black musicians who have shaped the classical music world

The Rainstorm Opus 6 by Thomas Wiggins ("Blind" Tom)

Bethune soon discovered Wiggins’ natural talent and decided to take the young musician under his wing, though for his own interest, not the child composer’s.

Neighbours reported that Wiggins would often practise for up to 12 hours every day; whether this was his own choice or not is unrecorded.

Wiggins began touring around the southern States as young as six years old, then from the age of eight, he was hired out to a concert promoter who sent him touring across the whole country, bringing in the promoter and Bethune sums of up to $100,000 a year (around $3.4 million today). It is thought that the Bethune family made around $750,000 ($25.4 million) from Wiggins’ talent in total.

Wiggins’ memory was excellent, and his repertoire was said to be over 7,000 songs long, with pieces ranging from hymns to classical music to popular music. He could listen to a piece and play it back almost immediately flawlessly.

Read more: 9 Black composers who changed the course of classical music history

Thomas Wiggins - Water in the Moonlight (1866)

Despite Wiggins’ excellent musicianship, the majority of media outlets criticised the man simply because of his race.

Even towards the end of his life at the turn of the 20th century, publications would praise his musicality and memory, but liken his talents to those of a performing animal. In 1904, the Tacoma Times maliciously reported, “Blind Tom, with all his music, is no more than a highly-trained dog or horse which can be made to perform for the public’s amusement.

“His music is a wonderful gift; it is not a mental quality.”

One year before the civil war, Wiggins became the first African American to perform at the White House, playing in front of President James Buchanan in 1860. Wiggins would have been just 11 years old.

During the war, Wiggins’ talents were reportedly used to raise money for the confederacy. Once of his most famous works, the Battle of Manassas, was written about a Confederate Army victory during the first year of the war.

As a result, many Black newspapers which launched after the emancipation of slaves, refused to celebrate the musician, as he only “served to reinforce negative stereotypes about African-American individuals” and that he had only a source of profit for slaveholders.

Thomas "Blind Tom" Wiggins - Battle of Manassas (1861)

After the civil war ended, Bethune took Wiggins on a tour of Europe when the musician was 16 years old. During the tour, Wiggins’ talents were observed by conductor, and founder of the Hallé Orchestra, Charles Hallé, who wrote that Tom was “quite marvellous”, “most remarkable”, and was a “most singular and inexplicable phenomenon”.

While the laws freeing all slaves in America were passed when Wiggins was a teenager, Bethune convinced his parents to sign a five-year agreement that gave the lawyer legal guardianship over the musician.

This “guardianship” from various members of the Bethune family, first the general, then his son, then his wife, remained until Wiggins death in 1908, though his birth mother tried and failed multiple times to release her son.

Wiggins continued performing up until 1904, when he suffered from a stroke that stopped him playing.

While the musician’s life was spent in the hands of others, his once in a generation talent inspired multiple Black, and visually impaired musicians.

Wiggins was one of the most celebrated Black concert performers of the 19th century, but is virtually unknown today, despite numerous books written about his life and documentaries.

No original recordings of him appear to exist, though the sheet music for his compositions are available, for musicians today to help keep his musical memory alive.