The time a gold treasure hoard was mysteriously found inside an upright piano

15 February 2021, 17:23 | Updated: 16 February 2021, 14:38

Presumably a different ilk of ‘note’ to what the piano tuner had expected to find that day.

Amid the hammers and strings of a run-of-the-mill upright piano at a Shropshire college, a local piano tuner happened upon a rather large stash of treasure in a remarkable discovery a few years back.

More than 900 gold sovereigns were found inside a Broadwood, that had been donated to the school in 2016 by a couple who were downsizing their home and had no idea of what had been sitting under the roof.

The following year, piano technician Martin Backhouse was hired to tune the 100-year-old instrument at Bishop’s Castle community college in Shropshire.

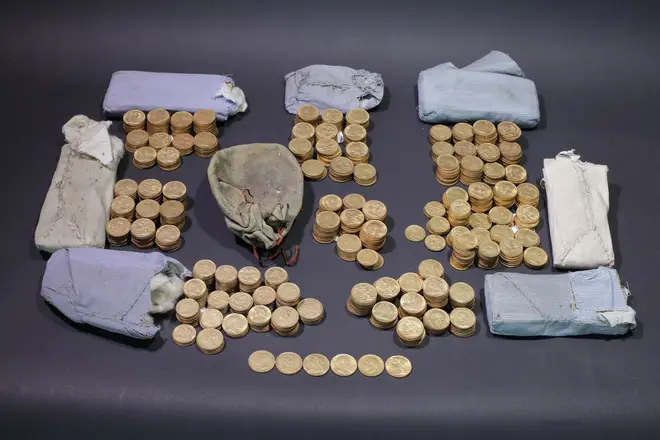

When he opened it up, Backhouse discovered hundreds upon hundreds of coins, carefully concealed in seven cloth packets and a leather drawstring purse.

They were later found to date from 1847 to 1915 and, numbering 633 full sovereigns and 280 half sovereigns, were deemed the largest stash of its kind.

It was officially declared as ‘treasure’ by Shrewsbury coroner John Ellery, as it was substantially made of gold or silver and deliberately hidden by the owner with a view to later recovery, and its owners, or heirs or successors, remained unknown.

Read more: Listen to the ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata on Beethoven’s own piano >

A major search was carried out, but the coins’ original owner, or the reason for them being stashed away so curiously, remained a mystery. An inquest heard that 50 people coming forward to lay claim to the hoard, but no true claimant was found.

While the crown now has ownership of the treasure, the tuner and the college shared a reward from the find.

Backhouse said it was likely the piano had not been tuned or worked on since its manufacturing in 1906. “I found the keys were a bit sluggish, so, as a technician, what I do is take all the keys out,” he told The Guardian.

“When I started taking the keys out at the top treble, I thought ‘what’s that packaging underneath? That’s old. That’s white corduroy.’ Then I noticed it was very nicely stitched. I thought ‘well, that can’t be moth balls’.

“I lifted one out. It was very nicely wrapped, very stiff, all neatly designed specifically to fit in the piano. Very carefully done and very heavy. I cut off the end with my penknife and it was gold coins.”

He put it all back together and went to find the headteacher. He then pulled out the rest of the keys “and we really discovered the size of the hoard then”.

In total there was equivalent to more than 6kg of gold bullion.

Peter Reavill of the British Museum’s Portable Antiquities Scheme called it a “stunning” find and estimated at the hearing that the stash could be worth hundreds of thousands of pounds.

The whole hoard was finally valued at around £500,000.

“The current owners did not know what to do but they came to the museum and they laid it all out on the table,” Reavill said. “They laid this stuff out and I was like ‘whoa’, I’m an archaeologist and I’m used to dealing with treasure but I'm more used to medieval broaches. I have never seen anything like that.”

He added the objects appeared “to have been deliberately hidden within the last 110 years”.

Reavill also told the hearing the hoard was likely repackaged between 1926 and 1946, because one of the packets contained an old Shredded Wheat advertising card from that era.

Beethoven played on a Broadwood Piano

The piano’s history is, as a whole, a little mysterious. It was sold to two music teachers in Saffron Waldon, Essex in 1906, but there is no further record of it until 1983, when it was bought by the Hemming family.

Graham and Meg Hemming moved to Shropshire and, when their children had left home, donated the piano to the college in the summer of 2016, to help students practise music. The couple owned the piano for 33 years, with no idea of what was inside.

They said they were “very happy” the money would go to the college. “We hope they will do something that benefits the children's musical ability – we feel very strongly about that,” Mrs Hemming said at the hearing.

She also expressed disappointment that the heirs to the treasure had not been traced, saying: “It’s an incomplete story – but it’s still an exciting story.”

The last we hear of the treasure, is that at least a portion of it eventually returned home in 2018, after a museum in Saffron Waldon launched a successful bid to buy part of the hoard.