On Air Now

Early Breakfast with Lucy Coward 4am - 6:30am

21 July 2022, 18:22 | Updated: 5 August 2022, 17:17

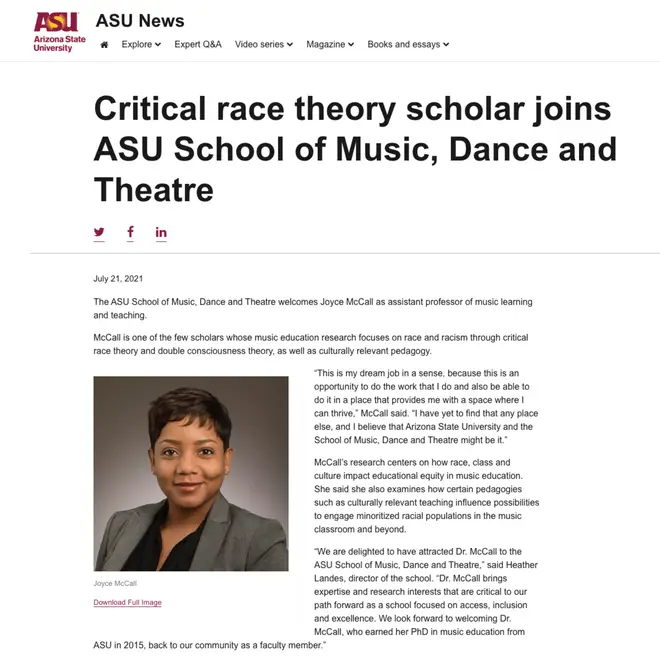

One year on from Dr Joyce McCall’s widely publicised appointment at Arizona State University, we speak to her about her specialism in Critical Race Theory and why this subject has become an integral addition to arts education.

Dr Joyce McCall serves as an assistant professor in Music Learning and Teaching at Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona.

The Arizonan university announced her appointment one year ago on 21 July 2021, and Dr McCall was met with a backlash, namely from far-right media, regarding her new position due her specialism in Critical Race Theory.

We speak to her one year on, to learn why Critical Race Theory is needed in music education, why her appointment received such a shocking response, and what Dr McCall believes needs to change in the field.

Read more: 63 percent of Black musicians have experienced racism in UK music industry

“Critical Race Theory is a tool that was conceptualised and born out of critical legal studies as a means to analyse, critique, and to help dismantle racism,” explained Dr McCall.

The term has been widely shared, but also widely misused, particularly over the last year in relation to school curriculums, becoming a fierce debate about how children should be taught in America, and elsewhere across the world.

In relation to music, Dr McCall explained, “Even though we try to push forward, and [musical institutions] like to think of ourselves as being more progressive and more innovative, pushing out those boundaries. When you look at a university curriculum in America, it gives you a really nice snapshot of Western Europe. And so not only does that represent a type of voice, but aesthetics, the culture, the history, the people.

“So if you can’t perform that type of music, or use your instrument to articulate that particular sound and those musical ideas, then your chance of getting into a music school in higher education in our country is pretty small.”

Read more: Society dedicated to ‘preserving’ Western classical music sparks accusations of racism

“I’m one of these scholars that plugs Critical Race Theory into music education and asks ‘What does systemic racism look like in this field?’, ‘What’s the impact?’, ‘Who’s benefitting from it?’, and ‘Who’s not?’.”

Dr McCall gained her undergraduate degree in performance before going on to serve as a clarinettist and saxophonist in the United States Army Bands from 1999 to 2013. She then went on to earn her PhD in music education from ASU in 2015.

Growing up in a predominately Black neighbourhood, Dr McCall was aware of the difference between the music curriculum she was leaning at school, and the music she was surrounded with at home, from a young age.

“As a kid, Saturday mornings was cleanup day,” Dr McCall recalled. “You made your bed, you tidied up, and my folks would put on LPs while we cleaned. So on Saturdays, we’d be listening to The Temptations, and Aretha Franklin. You’d hear the blues.

“My dad got me a clarinet in the fifth grade, and when I brought home music to practise from school, [for orchestra], he would say, ‘Why do you keep playing that same boring music over and over and over? Why don’t you play ‘When the Saints Go Marching In’? Why don’t you play The Temptations?

“He didn’t understand that that wasn’t the music we were learning in school, or maybe he did understand, and that was his way of calling it out.

“Instead of learning music from like BB King or Bobby Womack, we were learning ‘Hot Cross Buns’. And folks in my neighbourhood who always be like, ‘Man, y’all always playing that white people’s music’.”

Read more: Did you know Aretha Franklin once stepped in for Pavarotti… and sang Nessun Dorma?

Trailer for Aretha Franklin biopic 'Respect'

“So I learned early on that it wasn’t just about what we were playing, but who was playing in these ensembles with me. I was one of very few Black kids in band.

“Then as I moved through college, my masters, PhD, and especially, even in the military, I was one of very few Black folks, in these ensembles.

“In the military, I think two of the four units I served in, I was the only Black female. And so it’s very stark, as you sort of matriculate up.”

“I’ve never played the Mozart Clarinet Concerto,” Dr McCall told Classic FM. “That’s something I tell students a lot. As a student, as you move through the ranks at a university, there are certain pieces you have to play. For the clarinet, that’s the Mozart, and I thought, ‘everyone and their mama has played these tunes’.

“I remember telling this to my undergraduate clarinet professor, and he argued that the piece was a standard. I said, ‘If I find different music, will you support me playing something different?’ and I was able to make it through my college degrees without ever playing the Mozart in a formal space.

“By [only focusing on this music], we’re just emphasising and saying explicitly and implicitly, that only this music is good enough.”

So how do we make sure the curriculum continues to evolve? While many music departments across the world are adding one-off modules such as hip-hop and jazz to degrees focusing primarily on western music, Dr McCall says there’s an easier way to fix this.

“You can throw a rock and hit a DJ,” Dr McCall laughed, “you can throw a rock and hit a jazz musician who's incredible.”

Read more: Mozart’s best music – 15 of his greatest works

Brahms sextet for clarinet, string quartet and mobile phone

“But I know some professors who are teaching right now, at universities, who are teaching rock and roll who are taking hip-hop and other people’s music, and they have no cultural connection with that music whatsoever. And they’re doing a bang-up job with it in the worst way.

“So change will come when top people in the administration say, ‘we want the best people for this job. And the best people don’t have to have a PhD. But they do need to have a critical consciousness, the ability to really stimulate students, and to help develop, alongside students, their cultural competence about their own music and about other people’s music.

“I previously taught a jazz methods course at the University of Illinois, and I taught it the way that I learned how to play jazz and improvise. For me, that was all about movement, and also knowing the stories that that helped to make that music come alive.

“It was so interesting to find out that students who have previously played jazz in high school, could only play the notes. Sure, they could talk about Duke Ellington, but they couldn’t distinguish his music from Count Basie.

“So I'm all about empowering future scholars and future music teacher educators to push out against how they teach this work.”

Read more: Charles Mingus at 100: a legendary jazz musician with classical music roots

Dr McCall has observed how music is taught at historically Black colleges and universities and says the way music is taught is different to how the subject is approached in predominantly white institutions.

“Professors I’ve observed teaching at HBCUs, talk about music in a very culturally relevant way, but specifically in a way that makes sense to their students and helps them to create these bridges of understanding.

“They’re providing an opportunity for students to critique the music, and to critique why this music is placed on a pedestal. We can keep teaching Brahms and Beethoven and Stravinsky and you know, a whole lot but we have to be critical of that music and ask, ‘Well, why do we put it on this pedestal?’ That’s something we should be asking about regardless of the genre of music.”

“I sat in at Texas Southern University, an HBCU in Houston, Texas, in the class of Dr. Darrell Singleton. He was using Pierre Bourdieu to talk about cultural capital theory, but he also used Beyoncé and Jay Z to talk about the same topic.

“Critical Race Theory is about the method of delivery, not just about what you’re teaching; it’s about how you’re teaching, and that you’re conscious about whom you’re teaching.”

Read more: When Beyoncé showed us mere mortals her full operatic voice

In 2016, the head of the National Association for Music Education left his post after being reported saying that “Blacks and Latinos lack the keyboard skills needed” for a career in music education.

“Here’s the thing,” Dr McCall commented on the event, “I wasn’t upset by it.

“This has always been the message within music education, but someone finally said it. It was like the drunk uncle at the Christmas party, just saying out loud what everyone else was thinking, implicitly, through their actions, or through their lack of actions.

“The reaction was really dramatic, folks actually started burning their membership cards online. But what’s happened since then? Not much has changed in music education.

“We’ve moved shifted a few things, but have we have we turned things around? For the better? I would say no.”

Read more: How the murder of George Floyd impacted music-making in Minneapolis and across the globe

When Dr McCall was hired in 2021, she “anticipated pushback”, because “that’s part of America. There are people who don’t mind sharing their views, views that are steeped in racism.

“When I was appointed, I got emails from random people, disgusting emails.”

Dr McCall’s appointment was questioned by some media outlets, with commenters saying that music wasn’t racist. And to a certain degree, she agrees.

“Notes aren’t racist. A [quaver], a [semibreve], they aren’t racist, but it’s how we use those things. We weaponise Western notation to keep some people out, and to welcome others in. Because if you can’t read notation, you can’t get into the music schools.”

“I’ll never forget, I was in Chicago, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra had just finished playing a concert. The concert-goers coming out of this concert would have paid maybe $200 (£167) to listen to this gig, and when they were leaving the building, a Black homeless gentleman in a wheelchair, on a tuba, was playing exactly what they had just heard from the symphony orchestra.

“But instead of stopping and listening to the music like they did in the concert hall, they passed by him, turning their noses up. One lady tried to get security involved and get him him removed from the sidewalk.

“People know what they’re doing, and they think it’s subtle, but it’s not.”

Read more: ‘Black trauma for white entertainment’ – new opera about lynching faces racial backlash

“Some days, I want to walk away and do something else”, Dr McCall admitted. “I think, I’ll take my talents and plug them in somewhere else, and do this same sort of work in a different way, with a different group of people, and sit at a different table.”

So why does McCall keep doing what she’s doing?

“I can walk away or I can speak truth, in a way that’s brutally honest, and teach classes that provide folks to move out into the world with better tools to teach. I stay for those Black scholars. I want students to have somebody they know who in terms of, for instance, scholarship, write a certain way.

“And you know, maybe if I cared about people’s feelings in the comment section of those articles about me, maybe I’d feel differently.

“But I take a leaf out of my grandmother’s book. She was this honest little lady, and she didn’t care about people’s feelings.

“That’s why I stay, and work for a better future. I cannot look at students, look them in the eyes, knowing that I haven’t done my best to help change this field.”