On Air Now

Classic FM Breakfast with Dan Walker 6:30am - 9am

25 March 2021, 12:56 | Updated: 25 March 2021, 13:15

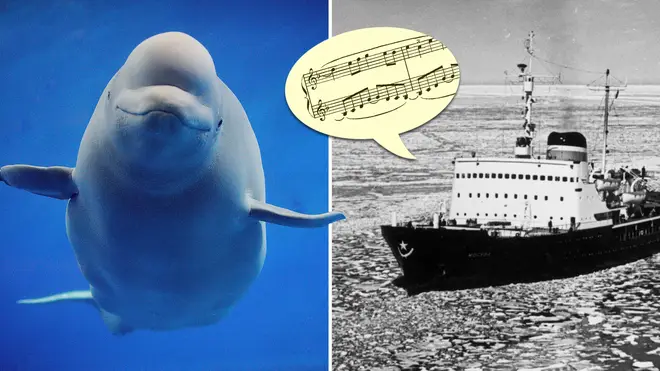

By playing classical music through a loud speaker, the ice-breaking ship Moskva was able to guide 2,000 beluga whales to safety.

In 1985, a herd of beluga whales found themselves in a life-threatening predicament: they were trapped by a wall of ice and were at risk of suffocating or starving to death as breathing pools began to shrink.

Facing a race against the clock, a ship called Moskva – the world’s toughest icebreaker at the time – was called in to help the mammals by breaking through the thick ice.

But when the 13,000-tonne vessel reached the whales, they were too frightened by the roar of its engine and deafening propellors to follow it to their freedom.

The ship’s crew members were at a loss for what to do, until someone made a wild suggestion... to play classical music.

Beautiful music soon echoed from the Moskva’s top deck from a loud speaker, and sure enough, the whales began to follow.

Read more: Flautist coaxes whale to the surface (and it almost knocks her over) >

Writing about the incredible feat at the time, The New York Times shared some of the details published by Russian newspaper Izvestia.

“This operation was truly experimental,” the Times wrote.

Read more: Whale tail artwork saves train plunging into water in Holland >

“At last someone recalled that dolphins react acutely to music. And so music began to pour off the top deck. Popular, martial, classical.”

The broadsheet continued: “The classical proved most to the taste of the belugas. The herd began to slowly follow the ship.”

Watch these talented scuba divers perform music under the sea

Read more: These whales responded to a cello being played, and it's incredibly beautiful >

In the end, it was estimated that around 2,000 whales managed to escape an untimely death.

The rescue mission later became known as ‘Operation Beluga’, and cost the Soviet government about $80,000 (£58,302).

Beluga whales routinely hunt and hide beneath thick ice, but they must surface every twenty minutes or so to inhale air.

A wonderful marriage of music and nature. We wonder what they were played – ‘Deeply wailing’, perhaps?