On Air Now

Calm Classics with Myleene Klass 10pm - 1am

13 March 2020, 13:43

Louis Braille, the inventor of a tactile reading method for people with visual impairments, also invented braille music notation. Here’s everything you need to know…

In 1829, Louis Braille invented a tactile reading method for blind people to read and write. He adapted it from Captain Charles Barbier’s “night writing” system, which he thought had room for simplification.

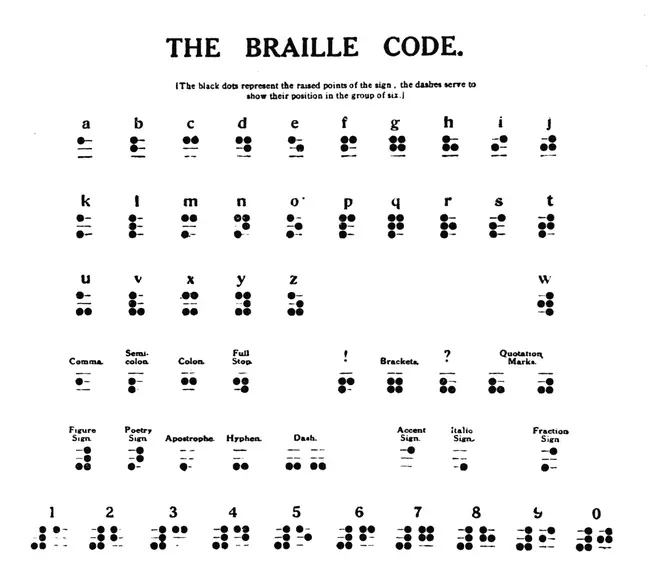

Braille took the 12 dots developed by Barbier, and simplified them into six for his own tactile method, which is known simply as braille.

Crucially, it is not a language, but rather a code that people can use to read and write all languages.

Read more: Meet BSO Resound, the ensemble of disabled musicians changing the classical music world >

Braille uses a six-dot matrix to present tactile representations of letters of the alphabet.

“It just looks like the six dots of a dice [sic],” Kate Risdon, flautist at BSO Resound, tells Classic FM (watch video above). “It fits conveniently under the fingertip so it’s a convenient size to actually read.”

All the letters of the alphabet correspond to different combinations of dots (varying in number and placement), and these can be “read” with the finger to form words, sentences, phrases and extended texts.

Read more: A glossary of useful classical music terminology >

Louis Braille adapted his tactile reading system for music and mathematics by adding extra symbols.

“He did it in a linear and a literary way, rather than using a graphic score as print music would,” Risdon explains (watch above).

“Being French, Louis Braille would have thought in terms of ‘do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti”, she says – and in French ‘do’ is always the note C.

It made phonetic sense to Louis Braille to assign D for ‘do’ and carry on up the scale using the next letters of the alphabet – so, E would be ‘re’, F would be ‘mi’, G would be ‘fa’ and so on.

“Which confuses English students to no end, because the note B corresponds to the letter J (ti), so we have to stop thinking like that and treat it as a separate bit of coding,” Risdon says.

She goes on to explain that the seven letters representing the do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti notes in braille only use the top four dots of the cell, leaving the bottom two indicate note length.

Using only the top four dots automatically indicates quavers (eighth notes), while you use the bottom two dots to indicate minims (half notes) or crotchets (quarter notes).

It gets complicated, Risdon explains, where you run out of options and note lengths double up. Semiquavers are notated as semibreves, demisemiquavers are the same as minims and hemidemisemiquavers are the same as crotchets.

The system works because the notation would include a time signature that can be used to indicate which length the notes are according to logic – for example, you couldn’t have sixteen semibreves in a four-four bar, so they must be semiquavers.

Aside from rhythm, other performance indications are described in the score.

There’s a system of octave signs that precede the cells denoting pitch, as well as indications of performance markings (speeds, dynamics, and other directions), and other descriptors found in scores.

“Before you get any of your notes, you have a lot of other things,” Risdon explains in the video above.

As well as the tempo indication, there are key signatures, bar numbers and section markings – which are of course invaluable for rehearsing in ensembles.

“Incidentally,” Risdon adds, “the sharp, flat and natural signs are used exactly as they are in print music.”

The short answer? You don’t.

Risdon is a member of BSO Resound, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra’s professional ensemble formed by disabled musicians, and she relies on braille music scores to learn new pieces.

“It starts with reading and singing,’ Risdon explains. She also uses a computer to enable her to listen, read and then play (watch above).

It requires reading the score first, listening to a recording of the piece and, once the tactile markings are committed to memory, picking up your instrument to play along.

Repetition of this process – plenty of reading, listening and having a go – allows braille-reading musicians to learn their score. Watching Risdon’s demonstration in the video above really illustrates the steps it takes. “A lot of sitting with YouTube, headphones, and a cup of coffee!” Risdon summarises.

Speaking with Risdon, we get the privilege of seeing a selection of different braille scores – some new and bright white, others older and the colour of tea, and hand-brailled a long time ago.

Publishers are increasingly catering for visually-impaired musicians and producing their scores in braille.

The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (ABRSM) publishes flute and piano exam pieces in braille, and the Royal National Institute of Blind People also loans and produces braille music.

Click here for more braille music resources and information from the UK Association for Accessible Formats (UKAAF).

BSO Resound is the disabled-led ensemble at the heart of Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Classic FM’s Orchestra in the South of England. Allianz Musical Insurance is a supporting partner of BSO Resound.