This is how Beethoven can change your life – we meet the legendary conductor Herbert Blomstedt

20 October 2017, 16:43 | Updated: 20 October 2017, 16:45

Herbert Blomsted is a true icon of classical music. He celebrated his 90th birthday in July this year but he’s just recorded all nine of Beethoven’s symphonies, will be performing at the Barbican this month and isn’t thinking of retiring any time soon…

How did you decide to become a conductor?

Unlike some of my colleagues, I did not dream of becoming a conductor. I loved orchestra music – when I was at school I listened to two symphony concerts a week in Gothenburg. But I played the violin and I was more fascinated by playing the string quartets of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. My brother played the cello and tougher we dreamed of find a couple of lovely girls who played the viola and violin, and we’d find two houses by a lake and play string quartets every day.

Of course that didn’t happen. The real change in direction came when I studied at the conservatory in Stockholm and I was chosen to conduct Brahms’ Requiem one semester. That was the beginning of it.

What’s your advice for young musicians just starting out on their careers now?

Get a good musical training, whatever musical instrument you play. I was a violinist and then an organist also. But it doesn’t matter so much what instrument you play, but that you have to get a very good musical training and knowledge of theoretical subjects – harmony, counterpoint and so on. Only if a conductor starts out as a good musician does he stand any chance. To start too early to wave your hands in front of a professional orchestra doesn’t bring much. You might get some flashy emotional things if you conduct a Mahler piece, but conduct a minuet from Haydn and see if you can get some music out of that.

Herbert Blomstedt shows his… musical side in this video from the Berlin Philharmonic:

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever been given?

My piano teacher at the conservatory gave me some great advice He was a pupil of Artur Schnabel. He said: you have to hear the tone in your head before you strike the key. Don’t just push down the key and then discover how it sounds, but have in your head already how you want it to sound, then try to transport it to your fingertips.

That’s very good advice for conductors too. You must never give the downbeat and then say to your self “now, how does that sound?”. You must know how you want it to sound before you even pick up the baton.

You’ve made a huge amount of recordings in your career. Is there one which stands out for you?

First, I must make a confession – I don’t listen very much to my own recordings. But I do especially remember when we recorded Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony in Dresden with the Staatskapelle. We had been on tour in Japan for three weeks and had played the symphony several times on tour. And when we came back to Dresden to record this piece, of course we didn’t need to rehearse at all. We just had three days to adjust to the time different and then we went into the studio and recorded this. And it’s a fantastic sound. When I listen to the end of the first movement, when you start the final crescendo, how the orchestra plays fills me with awe.

Is there a recording you’d like to go back and do it again?

Yes and no. I cannot mention a particular piece but we’ve just finished recording the Beethoven symphonies for the second time. I recorded them in Dresden 30 years ago and many things have changed since then – I have changed, the editions have changed, the orchestral seating has changed. At the time of the Dresden recordings we had the second violins sitting inside the first, but that’s not correct. In Beethoven’s time you have the second violins on the right, otherwise you cannot have the dialogue between the first and second violins.

So when I returned to these symphonies I wanted that sort of sound geography and now we also have the big advantage of using the new editions. We use the Bärenreiter editions edited by Jonathan del Mar which I think is the best edition you can have nowadays. That brings a lot of information you we didn’t have 30 years ago, particularly the metronome markings.

Why do you think audiences and musicians still love Beethoven’s music?

I think the most striking character of Beethoven’s symphonies is the will power – the resolute plan for every work. He takes us by the hand so to speak and leads us his way. It’s music that has a message, but you have to work to find that message. If you just play the notes, that does not mean that you’ve got the meaning of the music.

What role do you think music has in a politically divided world?

Music can certainly split people but it can certainly also bring people together. Music has a very big impact on the listener.

I know from many reactions I’ve had from the public how it can change people's minds and even change their whole lives by listening to a Beethoven symphony. I’ve been performing in Tokyo every year for about 40 years. Some 15 years ago I got a letter from a banker and he said he’d been thinking of committing suicide because he was so unhappy with what was happening in the world of banking – so much fraud. He was thinking, I’ve devoted my life to a business where so many bad things are happening, I cannot go on like this.

And he came to one of our concerts where we played a Beethoven symphony and it changed his life. He said, “if there’s a world where Beethoven could create this music, some 200 years ago, it must also be possible to give my work in the world a good purpose.” He was sensitive enough to understand the different moods in the music and was carried along with its sense of purpose. The music changed his life. And now every time I come back to Tokyo there’s a big box of fresh fruit waiting for me.

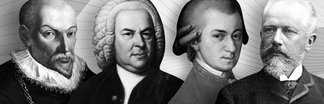

Finally, if you could go back in time and meet any of the composers from the past for a coffee, who would it be and why?

This is a difficult question, I would like to meet many of them! Since I was a violinist from the beginning, Bach was my musical god. The incredible talent and incredible mind – of course he was a very religious man. He was convinced that music was of divine origin and he had had divine purpose in his composing of music. The other one is Schubert. Schubert is a mystery to me – he is an incredible artist, every bar is so wonderful and fresh. Schubert composed as if he had some secret line to God himself. The second movement of his String Quintet always makes me cry. It’s so musically perfect and enigmatic that it brings me awe and wonder.

Herbert Blomstedt conducts the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig this Sunday, 22 October, at London's Barbican, at 7.30pm.

His latest recording of Beethoven's symphonies is out now.