On Air Now

Relaxing Evenings with Zeb Soanes 7pm - 10pm

26 March 2018, 16:44 | Updated: 1 April 2021, 15:12

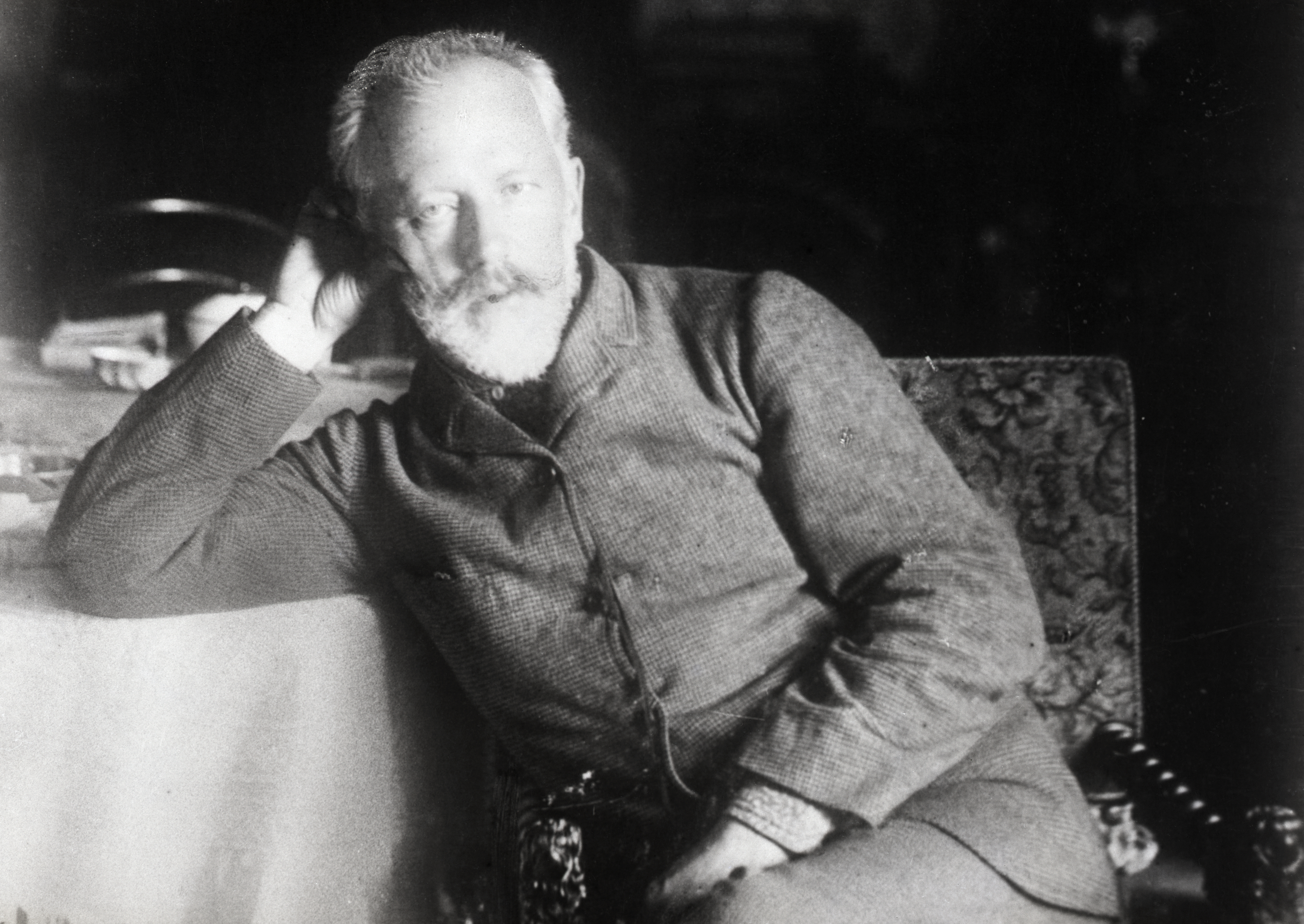

Though he loathed it, Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture won him fans the world over and made him a household name.

In 1962, a Don Draper-like advertising executive decided to market the oaty goodness of an up-and-coming brand of breakfast cereal by detonating bowls of it from a cannon in time to the finale of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture.

When Arthur Fielder led the Boston Pops through the same piece in 1974, during a televised 4 July concert, the 1812 Overture was elevated from advertising prop to full-on national anthem, one still performed today to mark American Independence Day.

Woody Allen co-opted it for the soundtrack of his 1971 screwball comedy, Bananas. It has been referenced in The Simpsons and in 1967, British comedian Charlie Drake struck comedy gold when he ‘performed’ all Tchaikovsky’s instrumental parts and ended up in an exhausted, Norman Wisdom-like heap on the floor. Each re-imagining took us further away from the 1812 Overture as Tchaikovsky understood it.

Read more: A beginner’s guide to Tchaikovsky’s ballet Swan Lake >

That infamous assessment of it as “very loud and noisy and completely without artistic merit, obviously written without warmth or love,” was penned by Tchaikovsky himself. The overture’s popularity was a source of deep frustration to this sensitive, serious-minded symphonist whose imaginative fantasy and whimsical, melodic turn of phrase had also managed to transform the art of composing ballet music to a high calling.

The success of the 1812 Overture told him that the world cared more about theatrical spectacle than the hard fought-for personal expression of his symphonies, concertos and chamber music. The more successful his overture, the more Tchaikovsky became convinced that the world fundamentally misunderstood his art.

The piece is drenched in proud nationalist sentiment; Russian folk songs are heard to chase the French national anthem, The Marseillaise, before obliterating it in sound. It has become fair game for ‘pop classics’ concerts to trade off its showbiz pizzazz.

Tchaikovsky’s climactic cannon shots are used to trigger indoor fireworks, acrobatic displays even. The populist ante is constantly upped. 1812 Overture On Ice? Underwater 1812 Overture? Celebrity 1812 Overture On Ice, The Musical? It’s only a matter of time.

But what happened to the ‘real’ 1812 Overture, and how did Tchaikovsky come to write his Frankenstein monster? It is the 1812 Overture because it was conceived to commemorate the Battle of Borodino, fought in September 1812.

In the 1880s, Russian pride still glowed at the warm memory of Tsar Alexander I’s troops thrashing Napoleon’s army, although there was a certain level of rose-tinted hindsight going on here. Napoleon had retained the tactical upper hand throughout the battle itself, and was only forced into a long and arduous retreat when, during his subsequent occupation of Moscow, food supplies ran out as winter started to bite. Armies march on their stomachs, and Napoleon’s men marched out of Moscow to fill theirs.

... and a cunning plan from Tchaikovsky’s champion and mentor, Nikolai Rubinstein. The Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, which had been commissioned to celebrate the Russian victory – never mind the nitty-gritty specifics of the battle itself – was nearing completion on the banks of the Moskva River in central Moscow. Rubinstein’s request to Tchaikovsky might have gone something like this:

“Compose a ‘go to’ commemorative composition and fill it with national themes. Make it a ‘useful’ occasional work to be performed to mark the opening of the cathedral. And the 25th anniversary of Alexander II’s coronation. And don’t forget about the 1882 All-Russian Arts and Industry Exhibition. They’ll want something too...”

Tchaikovsky cranked out the 1812 Overture in six weeks, cutting his imagination loose with every note and theme designed to tug at Russian heartstrings. And although the most celebrated section of the work is inevitably Tchaikovsky’s flamboyant, proto-cinematic finale, its opening passage is equally spectacular – albeit spectacularly understated.

Needing to ground the music in some fundamental truths about the Russian mind and spirit, Tchaikovsky opens by recalling a soulful Orthodox hymn, ‘Troparion of the Holy Cross’. A lesser composer might have sentimentalised the harmonies, but Tchaikovsky places this objet trouvé delicately on four violas and eight cellos, like an ethereal and wistful sound borrowed from the memory bank of history.

... that the 1812 Overture is better than Tchaikovsky realised and, despite the indignities and abuse it has suffered in the name of entertainment, his score is robustly constructed and has maintained its compositional integrity. Because the opening sets the scene so powerfully, Tchaikovsky has access-all-areas to go anywhere musically as he begins to portray the shattering impact of the French invasion on his country.

A Russian folk dance, ‘At The Door, At My Door’, trumpets national pride; pride that is rocked by the first appearance of The Marseillaise, characterised as mocking and provocative, which Tchaikovsky shoots down with five strategically aimed cannon shots.

In a late, great symphony like his Fifth or Pathétique No. 6, Tchaikovsky’s melodic invention rises to the surface as his themes are combined in counterpoint: polarised logics of the symphonic argument made to coexist or not, and Tchaikovsky’s genius for eloquent counterpoint is woven into the fabric of the 1812 Overture at a deep structural level too.

With the battle gathering force, another Russian theme emerges, God Save The Tsar!, which he manoeuvres into a contrapuntal skirmish with The Marseillaise: two nations fighting it out in music, the composer never allowing the contour of one theme to nestle too cosily against its adversary. Enemy lines are kept tautly demarcated. A plunging, descending string line symbolises the Russian retreat; cannon shots and cathedral bells peel over a victorious roar of God Save The Tsar! from the orchestra.

Tchaikovsky ought to have been proud. He had written the ultimate showpiece, but his faith in the 1812 Overture quickly unravelled. His aspiration to see it performed in the cathedral square, with a brass band marching on stage to clinch the climax – only to top that with cathedral bells and cannon fire – proved impractical.

Tchaikovsky hadn’t reckoned on a basic logistical flaw: that the arithmetic of exploding cannon shots in time to the music proved trickier than splitting the atom. A time lag between releasing the barrel and the shot sounding made shot-to-score co-ordination impossible. Then in 1881, the Emperor of Russia, Alexander II, was assassinated and triumphalist music suddenly seemed inappropriate. The work had its first hearing – indoors – at the Arts and Industry Exhibition two years later; no brass band, no cannon shots, no cathedral bells.

So what are the lessons of the 1812 Overture, much loved by an eager public but often mocked by musicians who play it, and even by its own composer? Perhaps that the person who wrote a piece of music cannot be trusted to give a reasoned opinion on it. Tchaikovsky failed to realise that it is impossible to take a piece back, or impose a view upon it retrospectively, once it leaves the composer’s desk. The material with which you once shared an intimate one-to-one relationship is in the public domain. It’s gone.

Manfred Honeck, principal conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (and a Tchaikovsky obsessive) remarked that most conductors play the March section of the Pathétique Symphony too triumphantly, when Tchaikovsky meant it to sound ambiguous and questioning.

There’s nothing ambiguous about the 1812 Overture of course; could that be why Tchaikovsky couldn’t comprehend the forces he had unleashed? For the rest of us, the 1812 is to be enjoyed in all its noisy, vulgar splendour.

The Battle of Borodino, the event that Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture commemorates, was the key battle of the Napoleonic Wars, and also its bloodiest. Seventy thousand troops perished as Napoleon’s army attacked the Imperial Russian Army outside the village of Borodino, west of Moscow.

Over a 24-hour period, the French bombarded the Russian Army, capturing the strategic points on the battlefield, but failed to destroy their enemy. Napoleon occupied the battlefield after the fighting was over, exploiting his position to launch an attack on Moscow, where he waited for over a month for a Russian surrender that never came. Napoleon hadn’t reckoned on the awesome chill of a Russian winter, and with food running out he was forced to retreat, handing the Russians victory.

In 1954, a studio recording was released that finally did the 1812 Overture justice. Hungarian conductor Antal Doráti and the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra used the authentic French muzzleloading cannon that Tchaikovsky had asked for in his score. It was accompanied by a documentary about how the cannon and cathedral bell effects were achieved, and how the cannon shots were co-ordinated.

This was the clear benchmark until, in 2007, Antonio Pappano released an intriguingly rethought 1812, performed with electric verve by the Orchestra dell’ Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (EMI Classics 637 0065).

Pappano’s concept was a historically re-envisaged 1812 Overture in which the hymn-based opening and anthem God Save The Tsar! are sung, rather than played.

It’s not what Tchaikovsky wrote but the sung sections put the music into context: how rooted the work is in the Russian soul through its choral tradition. Pappano doesn’t hold back on the cannon shots and bells, either.