Schumann - Piano Concerto in A minor: Full Works Concert Highlight of the Week

Jane Jones introduces the concerto that was saved for posterity by a virtuoso wife!

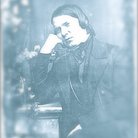

One of the most talked about partnerships in classical music must be that between Robert Schumann and Clara Wieck, the daughter of the piano teacher who mentored the young Schumann whilst he was staying with the family. Today, theirs is a relationship which might raise eyebrows, or stir the gossip’s tongues, but it seems that in those early days it was Clara’s talented virtuosity which attracted the lodger in the upstairs room.

The story of their love affair - which developed throughout Clara’s teenage years and ended in legal proceedings by her father in his vain attempt to split the pair - is well known. But with their marriage in 1840, there's a perceptible shift in pubic attitudes to Clara. She’s often portrayed as a self promoting artist, critical of her husband's attempts at composition and soft on Brahms! And she’s seen as a control freak who attempted to direct every aspect of both the personal and professional life of the Schumann family.

What is conveniently forgotten in this unsympathetic portrait is that Clara and Robert Schumann had eight children, cared for by Clara whilst she attempted to maintain a career of her own, and bring in some essential family income. Ultimately she became her husband’s carer as his mental state deteriorated until he was finally hospitalised.

So what has all this got to do with a piano concerto? Schumann’s Piano Concerto, begun in the year after they married, but not finished until 1845, was premièred by Clara and promoted by her in the face of considerable opposition after Robert died.

It’s an unusual work for its time, when the more formulaic concerto would pitch the pianist into a battle for supremacy against the assembled orchestra. The dramatic opening flourish might lead you to think this concerto will be more of the same, but Robert Schumann had written in the 1830s about his own ideas for how concerto writing for the piano might develop, and spoke of the genius who would make it happen. It turned out that the genius was Schumann himself!

That early piano flourish gives way to some beautifully understated melodies, and although there are passages when the piano reasserts its dominance, there’s no big bravura moment for the soloist to show off some flashy fingerwork. Schumann’s intention all along was to demonstrate how the piano and orchestra could work together, and there are some wonderful harmonies that underline those intentions.

But don’t be fooled! This isn’t a concerto which lacks passion and the exhilarating finale - with its interplay between soloist and orchestra - is an example of Schumann’s finest orchestral work.

Sadly, such a symphonic concerto wasn’t fashionable and audiences were left baffled by the lack of razzle dazzle – where was the wow factor? Clara in her diaries had praised her husband’s vision for the music, and as always her commentary encouraged him. In her concert programmes, Clara would always promote her husband’s music, and it’s thanks to the persistence of his virtuoso wife that Schumann’s Piano Concerto has now become one of his most popular pieces.