Rachmaninov: 15 facts about the great composer

A brilliant pianist, conductor and composer, Rachmaninov wrote a piano concerto that has become the nation's favourite piece of classical music.

-

1. A young, musical genius

Sergei Rachmaninov was born on 1 April 1873 in Semyonovo, north-west Russia. As a young man he consistently amazed his teachers with his jaw-dropping ability as a pianist and composer. He created a storm with his First Piano Concerto when he was just 18.

-

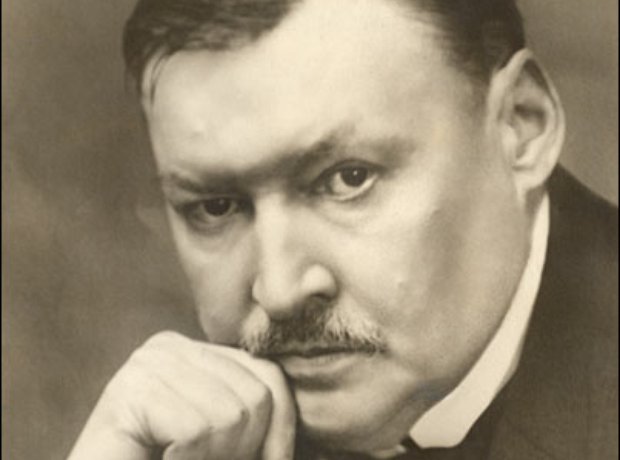

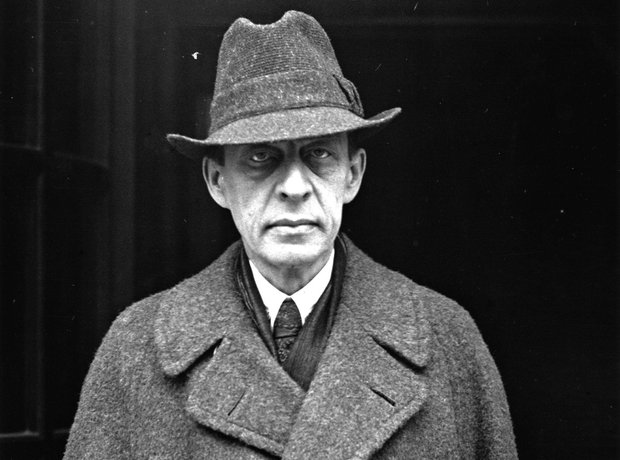

2. A drunken première?

The première of Rachmaninov’s first symphony in March 1897 was a total disaster. It took place under the baton of Glazunov, pictured, who was at best incompetent and, according to some, drunk. The critics tore the work apart and it was never again performed during Rachmaninov’s life. He fell into a depression and needed hypnosis to conquer the problem.

-

3. The nation's favourite classical work

Rachmaninov's Piano Concerto No.2 of 1901 is often described as the greatest ever written. Its subsequent use in the film Brief Encounter has made it a constant favourite. When Classic FM combined together the chart positions of the first 15 years of its annual Hall of Fame chart, the work came out on top overall as the nation’s favourite classical work.

-

4. Rachmaninov and daughter

It was after completing his first major choral work, Vesna (Spring) in 1902, that Rachmaninov made the surprise announcement that he was marrying his cousin, Natalya. This caused something of a stir as, in Russia, first cousins weren’t permitted to marry. But marry they did and in May 1903 their daughter Irina - pictured - was born.

-

5. Rachmaninov drawing

Rachmaninov was not just a composer, but in his day he was a fine conductor and magnificent pianist. He was appointed Principal Conductor of the Bolshoi Theatre in 1904 and was offered several major posts in the U.S. - most notably with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

-

-

6. A resounding success

Rachmaninov composed his Symphony No.2 in Dresden, where he and his family lived for the best part of four years from 1906. Writing the symphony was a daunting affair for the composer. However it was a resounding success and has remained one of the most popular of all of his works.

-

7. Enormous hands

The composer had possibly the largest hands in classical music, which is why some of his pieces are fiendishly difficult for less well-endowed performers. He could span 12 piano keys from the tip of his little finger to the tip of his thumb.

-

8. A shining hit

Rachmaninov's very large hands came in useful when performing his third piano concerto. It’s grander, fuller and more expansive in tone and style than the second – with the soloist stretched to the very limits of his ability. The work is used powerfully on the soundtrack of the film Shine and the success of the film ensured a new audience for this muscular, Romantic work.

-

9. A man of faith

Rachmaninov had a very deep and personal religious faith which he expressed beautifully in 1915 through his unaccompanied set of choral vespers. They are separated into two parts – the evening Vespers and the morning Matins, both full of exquisitely rich harmonies.

-

10. Driven out by the Russian Revolution

The 1917 Russian Revolution meant the end of Russia as the composer had known it. In December 1917, he left Petrograd for Helsinki on an open sled with his wife and daughters. Now in his 40s, Rachmaninov launched a third more lucrative strand of his career – as a concert pianist.

-

-

11. America - the future

Rachmaninov saw America as the future and from his arrival there in 1918 he found himself in great demand, so much so that composing became limited to the summer months. Things reached fever pitch in the 1922-23 concert season when Rachmaninov gave more than 70 performances between November and the end of March. He made enough money to build a house in Los Angeles that was an exact replica of his original Moscow home.

-

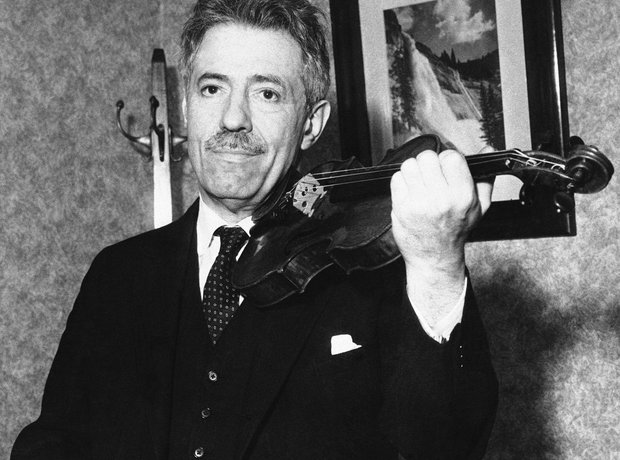

12. Lost in music

Rachmaninov was once giving a recital in New York with violinist Fritz Kreisler - pictured. Kreisler got into a muddle about where they were in the music. Panic stricken, he whispered to Rachmaninov. ‘Where are we’. The reply came back : ‘Carnegie Hall.’

-

13. The six-foot scowl

Despite his success, Rachmaninov seldom smiled in photographs. Tall and severe, he was once dubbed a ‘six-foot scowl’. He did however have a passion for fast cars - and later speedboats. He was the first in his neighbourhood to have an automobile.

-

14. Final recital

By the time of his final tour in 1943 Rachmaninov was already seriously ill. It seems almost prophetic that his final recital on 17 February 1943 included Chopin’s famous funeral march. He died of melanoma a month later in Beverly Hills, four days before his 70th birthday.

-

15. A lasting legacy

Only a decade after Rachmaninov’s death, the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians predicted that the ‘enormous popular success some few of Rachmaninov’s works had in his lifetime is not likely to last, and musicians never regarded them with much favour.’ They could not have been more wrong.