Scientists X-rayed Paganini’s favourite violin, to reveal the deep secret of its sound

13 March 2024, 16:24 | Updated: 13 March 2024, 16:29

The 18th-century violin, nicknamed ‘the cannon’ thanks to its powerful sound, is undergoing scientific tests to diagnose the root cause of its brilliance.

Listen to this article

Paganini’s favourite violin has been X-rayed by French scientists on a quest to understand how the instrument produces its miraculous sound.

Crafted by master luthier Giuseppe Guarneri in 1743, the instrument is now one of the most famous and valuable of its kind, having been insured for €30 million (around £25 million) for its recent trip across the Alps from Genoa to Grenoble.

The violin’s fame began when it was gifted to the legendary violin virtuoso, Niccolò Paganini, who had just lost a very expensive Amati violin on a bad gambling bet.

A wealthy French businessman and amateur violinist named Livron generously lent the violinist a Guarneri instrument he owned. After hearing the incredible sound Paganini could make on the instrument, he refused to take it back.

Paganini would play that Guarneri violin for the remainder of his life, nicknaming it ‘Il Cannone’, or ‘The Cannon’ after the instrument’s dynamite sound.

The two became so inextricably linked that today, the violin is known by many as ‘Il Cannone, ex Paganini’.

Read more: Niccolò Paganini was such a gifted violinist, people thought he sold his soul to the devil

Now, scientists and historians have united on a mission to unveil the violin’s secrets, determining what makes its sound so special and how to look after the historic instrument for centuries to come.

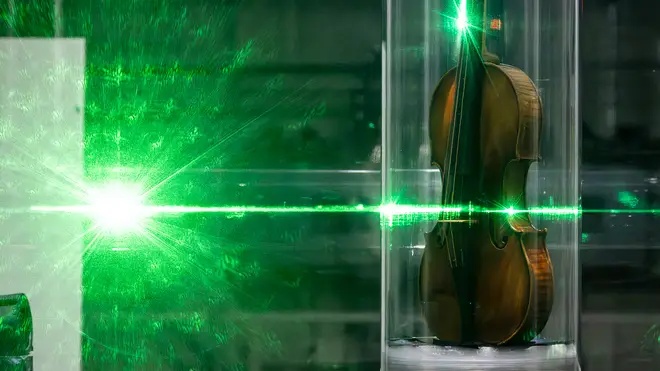

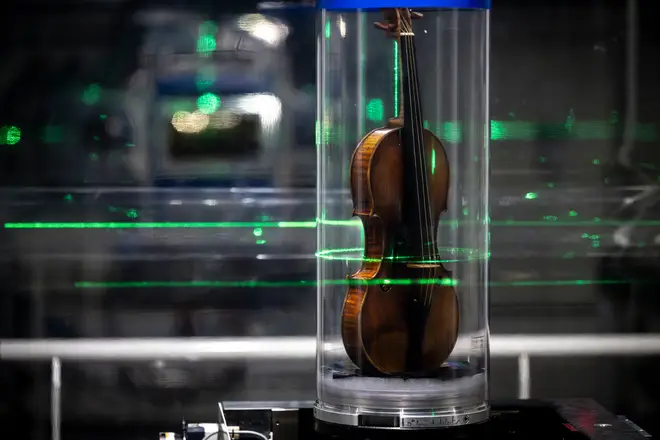

In order to understand the intricacies of the instrument, the violin was placed in a clear case while researchers at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) fired special ‘non-destructive’ X-rays at it.

Their aim is to discover the minute details of the wood’s structure to learn more about it, with results taking a number of months to materialise.

The study will also use an innovative new technique, allowing scientists to generate a hyper-detailed 3D rendering of the violin, with the possibility to zoom into an area the size of a micron – one-thousandth of a millimetre.

Luigi Paolasini, who is leading the project at the ESRF, said it “opens new possibilities to investigate the conservation of ancient musical instruments of cultural interest, as a crossing point between music, history and science”.

His colleague, Paul Tafforeau, described the job as “a kind of dream”.

“The first goal is conservation,” Tafforeau said. “If ever any flaws need repairing, we will have all the details. It’s an exceptional instrument in terms of its sound qualities. With this data we hope to better understand why.”