Mahler - Symphony No.5: 'A transforming experience'

Jane Jones looks forward to hearing Mahler's symphony, made more famous by a 1971 film.

There have been a few moments in the history of the cinema when a piece of music is integrated so perfectly that the images and the soundtrack become inextricably linked in the memory. As a result, the music becomes much more popular through its association with the movie than in its original context. Think of Rachmaninov's Second Piano Concerto in Brief Encounter or, perhaps less sublimely, Mickey Mouse's battle with the broomsticks accompanied by Dukas's The Sorceror's Apprentice in Disney's Fantasia.

Likewise the enduring popularity of the Adagietto movement from Mahler's Symphony No.5 - number 63 in this year's Classic FM Hall of Fame - certainly owes much to Luchino Visconti's 1971 adaptation of Thomas Mann's novella Death in Venice.

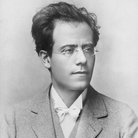

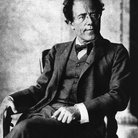

The Symphony No.5 emerged during a period of personal change for Mahler. He'd been enjoying great success as conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic but was forced to resign in 1901 after falling seriously ill. Towards the end of the year his fortunes changed again when he met Alma Schindler, an intelligent, artistic young woman whom he married in 1902.

Perhaps it was this unexpected brush with mortality, juxtaposed with the discovery of true love, that gave such poignancy to the Adagietto. Searching for a piece of music that would echo similar events on screen, Visconti not only used Mahler's music, but also took the liberty of turning Death in Venice's main character Gustav Von Aschenbach from being a writer to a composer.

Visconti skilfully uses the Adagietto to bookend the film. It sets the melancholic mood as Aschenbach's ship steams into Venice at the opening, and returns as the composer dies in the rain.

But of course there is much more to this five-movement symphony than just the one exquisite Adagietto. The fifth is the first of Mahler's symphonies in which he let go of a programmatic approach - so rather than dictating what the music should mean to us by providing some sort of narrative, the music suggests a kind of inner personal drama. The crucial Adagietto forms a hinge on which tragedy turns to triumph.

The emotional scope of the work is huge. After its premiere, Mahler is reported to have said, 'Nobody understood it. I wish I could conduct the first performance fifty years after my death.' Herbert von Karajan once said that when you hear Mahler's Fifth, 'you forget that time has passed. A great performance of the Fifth is a transforming experience. The fantastic finale almost forces you to hold your breath.'