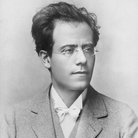

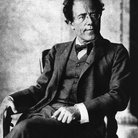

Gustav Mahler: A Life

The neurotic composer Gustav Mahler triumphed over appalling childhood memories and an obsession with mortality to become the last great Romantic symphonist.

Mahler’s lifetime spanned the most crucial period in musical history. Behind him lay the rich, Romantic pastures of Bruckner and Brahms, and ahead the “alien” musical landscapes of Schoenberg and Boulez and the harrowing emotional terrain of Shostakovich and Britten. Such was Gustav Mahler’s all-embracing vision that he earned the respect and admiration of all these composers.

During a conversation with Jean Sibelius, Mahler insisted that his symphonies were “whole worlds” embracing his literary tastes, his neuroses, responses to nature and, most especially, the inexorable cycle of life and death.

His four great song collections – Des Knaben Wunderhorn (Youth’s Magic Horn), Lieder Eines Fahrenden Gesellen (Songs Of A Wayfarer), Kindertotenlieder (Songs On The Death Of Children) and the five Rückert Lieder – all dwell on these very subjects, and also acted as a vital melodic repository for his symphonies.

Right at the end of his life Mahler fused song and symphonic form together in an epic Lieder-symphony entitled Das Lied Von Der Erde (The Song Of The Earth).

Each of Mahler’s nine symphonies (and the unfinished Tenth) requires the highest degree of orchestral virtuosity and sensitivity. He expanded the scale of music to near-bursting point – there are single movements in his works that last longer than an entire symphony by Mozart or Haydn.

He also stretched the traditional system of major and minor keys to its limits, taking music to the very brink of atonality (keylessness). Even 40 years ago, Mahler was still dismissed by many as a “fringe” composer, but now he is widely considered the last great symphonist in the tradition of Beethoven.

Mahler was born on July 7, 1860, in the Bohemian village of Kalischt, to a poor family of Moravian Jews. His father, Bernhard, ran a ramshackle distillery, and regularly thrashed his children and Mahler’s mother, Marie. She bore Bernhard 14 children in all and, despite suffering from a limp since birth and a heart condition, was made to work like a slave.

During a session with the pioneering psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, the deeply traumatised Mahler recalled running screaming from the house in agony to the strains of a hurdy-gurdy playing outside.

It is somewhat ironic that the physical scars left by his father amounted to little more than a severe bruising, whereas those left by his mother were to plague him to the end of his days. He suffered from a psychosomatic nervous tic in his right leg, which made his movements slightly ungainly, and he inherited his mother’s heart defect, the deciding factor in his death.

Although Mahler’s performance was only average in most of his school subjects, by his early teens he was already marked out as a pianist prodigy. At 13, he gave a sensational public recital that included a virtuoso note-spinner by Thalberg, and as a student at the Vienna Conservatory he performed Scharwenka’s ferociously difficult Piano Concerto No.1, apparently without batting an eyelid.

Mahler’s blazing talent unwittingly contributed to the great Lieder composer Hugo Wolf’s decline. The two shared lodgings as students, and formed a kind of mutual admiration society.

Sadly, by the end of his life, Wolf’s unstinting admiration for Mahler had dissolved into spiteful resentment at the latter’s success. Wolf’s descent into madness was marked by his wild claim that he had been appointed Director of the Vienna Opera and that his first job was to sack Mahler (by now the real director). Following a bungled suicide attempt, he spent the rest of his life in a Vienna lunatic asylum.

For a while, it seemed as though Mahler would make his way in the world as a concert pianist yet, following a series of whirlwind appointments in the provinces, he emerged as a conductor of visionary genius. His pioneering methods of concert preparation and opera production were to set the standard for the rest of the 20th century, exerting a profound influence on conductors from Herbert von Karajan to Leonard Bernstein.

Meticulous down to the last detail, a performance under Mahler was – like his music – all-encompassing. During his tenure at the Vienna Opera (1897-1908), he presided over 52 new productions of established repertoire, and introduced no fewer than 32 new works, including Puccini’s La Bohème and Madama Butterfly. As a result, composing became a part-time activity during the summer months between concert seasons.

Yet, if Mahler was universally hailed as a conductor, his music excited bewilderingly contrasting reactions, ranging from idolatry to near-revulsion. As early as the 1889 premiere of his First Symphony, opinion was already sharply divided.

A report that appeared in the Nemzet newspaper positively glows with enthusiasm: “This symphony is the impassioned work of a youthful, unquenchable talent, barely containing its seemingly inexhaustible ideas within a traditional framework... wild applause broke out at the end of every movement.”

Yet the New Pest Journal was altogether less enthusiastic, suggesting that audiences will “always be pleased to see him [Mahler] with baton in hand, just as long as he’s not conducting one of his own works”.

If the First Symphony caused problems, many of the following eight symphonies left audiences aghast – most particularly the Sixth with its chilling hammer blows of fate from the timpani.

Following the premiere, one critic noted painfully: “Where music falls short, the hammer falls.”

Yet not all was doom and gloom, by any means. The Resurrection Symphony No.2 won many fervent admirers, while the 1910 Munich premiere of the massive Eighth, the so-called Symphony Of A Thousand, was perhaps the single greatest triumph of Mahler’s career: “There was this extraordinary moment when, with thundering applause all around him, Mahler appeared in front of a thousand performers,” recalled the conductor Bruno Walter in his 1936 biography of the composer. “He mounted the steps of the auditorium towards where the children’s chorus was positioned... and shook every one of them personally by the hand.”

Other successes included an early Berlin performance of the enchanting Fourth Symphony, which Mahler himself conducted. Richard Strauss was so in awe of it that he sent Mahler his complete published works.

Mahler’s Fifth – from which the famous Adagietto comes – took longer to establish itself, but finally enjoyed an ovation in St Petersburg during Mahler’s tour of 1907. In the audience that night was the young Igor Stravinsky, himself on the verge of creating a sensation with the first of his great ballets, The Firebird.

Having conquered Europe, towards the end of his life Mahler was appointed Music Director at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. His constant battle with bouts of depression and neurosis had recently placed an appalling strain on his marriage to Alma, who was 19 years his junior, and he had never recovered from the death of their first daughter, Maria Anna, at the tender age of five.

Yet his new-found acclaim had a positive effect on Mahler almost immediately, and he began living for every hour.

In February 1909, Mahler agreed to revive the New York Philharmonic as a full-time professional outfit, typically insisting on the highest playing standards. On April 1, he conducted its inaugural concert, including a performance of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony that had the critics in raptures. He was immediately signed up as director, and given carte blanche to hire and fire.

Just as it seemed that Mahler might at last be coming to terms with the psychological problems that had plagued him all his life, he was diagnosed with a serious bacterial infection. The combination of his heart condition and the lack of antibiotics in those days meant there was no hope of recovery.

Mahler expressed a wish to die in Vienna and, having only just survived the transatlantic boat crossing, travelled by train to Vienna on a stretcher. Five days later he died, six weeks short of his 51st birthday. His last words, according to his wife Alma, were “Mozart – Mozart!”

He never saw Das Lied Von Der Erde or the Ninth Symphony performed and, despite the fame he had won against all the odds, he reflected despondently: “I am condemned to homelessness thrice over: as a Bohemian among Austrians, as an Austrian among Germans, and as a Jew throughout the world.”

DEFINING MOMENT

Mahler launches the main section of his First Symphony with this delightful melody, adapted from his Songs Of A Wayfarer. It is a classic example of how to compose a theme.

Mahler deliberately contrasts the opening six staccato (“detached”) notes with the legato (“smooth”) phrases that follow. But, out of contrast, he finds unity by deriving the downward scale [B] from the opening rising scale [A], and then repeating it a note lower. He returns to the little four-note figure [C] and repeats it three times [D], each time higher than the last. Yet it all sounds so simple!

Hear it on Mahler: Symphony No.1

London Symphony Orchestra, Georg Solti

Solti at his most engagingly charismatic.

Decca 458 6222