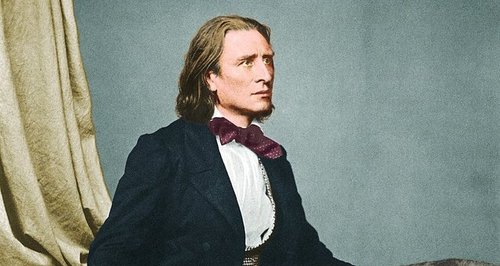

Franz Liszt: discover the great Romantic composer’s life

Franz Liszt combined sensational keyboard prowess, trailblazing creative inspiration and an insatiable love of life. Put it all together and you get a complex genius with the charismatic force of a musical tornado.

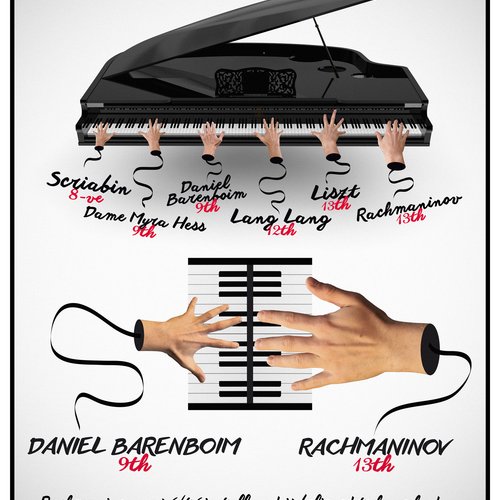

Franz Liszt was the greatest piano virtuoso the world has ever known. He literally redefined what 10 fingers were capable of, producing one scintillating sleight-of-hand keyboard effect after another.

Such was the sheer force of his musical personality that adoring women collapsed swooning following just a single touch of the ivories. Even the normally unimpressionable Matthew Arnold reported after a Liszt concert that “as soon as I returned home, I pulled off my coat, flung myself on the sofa, and wept the bitterest, sweetest tears”.

There were even those who thought Liszt’s unearthly powers were the result of a pact with the Devil, exacerbated by such dark and “paranormal” pianistic whirlwinds as the Dante Sonata and Mephisto Waltz.

Learning Beethoven’s C minor Piano Concerto from memory at a day’s notice, and sight-reading the score of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto with a cigar held between the first and second fingers of his right hand, were like child’s play to Liszt.

Yet he was more than a mere musical showman. He virtually invented the piano recital as we know it, ensuring that the ordinary man in the street got to hear music that was normally the exclusive preserve of the educated classes.

Orchestral concerts were still comparatively rare in the pre-gramophone age, so Liszt set about arranging many symphonic scores for solo piano (most famously Beethoven’s nine symphonies), in addition to composing countless sets of virtuoso fantasias on themes from operas, both popular and obscure. He was also a keen supporter of new music, and did much to establish the rising Nationalist schools in Russia and Bohemia, as well as encouraging the likes of Berlioz, Grieg and, most notably, Wagner.

Most mortals would have been more than happy to leave it at that, yet in addition to his colossal achievements as a virtuoso pianist, Liszt also composed in excess of 100 original titles for his instrument, many of which subdivide into sets of half a dozen pieces and more.

He created the orchestral symphonic poem, and as one of the first great modern conductors no longer content merely to beat time, he employed a vast repertoire of subtle and passionate gestures that revealed the music’s heart and soul.

He devised the leitmotif technique that Wagner used to mesmerising effect in his epic operas, while many of the novel textures we now associate with the Impressionism of Debussy and Ravel were in fact invented by Liszt.

“My piano is the repository of all that stirred my nature in the impassioned days of my youth,” Liszt once confessed. “I confided to it all my desires, my dreams, my sorrows. Its strings vibrated to my emotions, and its keys obeyed my every caprice.”

Liszt’s early progress was the stuff of legend. By the age of 12 he could play virtually anything at sight, and had won the enthusiastic approval of Beethoven when the young boy had played him his Archduke piano trio from memory, with the missing violin and cello parts incorporated as he went along.

Ignaz Moscheles, himself a front-rank virtuoso, wrote excitedly: “In its power and mastery of every difficulty, Liszt’s playing surpasses anything previously heard.”

Yet unbelievably, Luigi Cherubini, director of the Paris Conservatoire, refused him entry on the official grounds that he was a “foreign national” – in fact, Cherubini had an aversion to infant prodigies. Liszt never had another piano lesson.

Despite this early setback, Liszt remained based in Paris during the early 1830s (Chopin also settled there at this time), and became romantically involved with the Countess Marie d’Agoult (alias married popular novelist, “Daniel Stern”), who went on to have three children by him, including Cosima, who was destined to became both Hans von Bülow’s and, later, Wagner’s wife.

Yet by far the most notorious and celebrated period of Liszt’s career was between 1839 and 1847, when he gave well over 1000 concerts throughout most of western Europe, Turkey, Poland and Russia, stunning audiences wherever he went with his unique brand of pianistic devilry and showbiz razzmatazz.

A pair of white gloves was ceremoniously removed before each performance, a second piano was situated so that amazed onlookers could admire his prowess from every conceivable angle, and he would usually submit some trifling theme by a member of the audience to a series of breathtaking improvisations.

Something of the impact Liszt had on onlookers can be gathered from the celebrated Romantic poet Heinrich Heine, who coined the term “Lisztomania”: “When he sits at the piano and, having repeatedly pushed his hair back over his brow, begins to improvise, then he often rages all too madly upon the ivory keys and lets loose a deluge of heaven-storming ideas, with here and there a few sweet-smelling flowers to shed fragrance upon the whole. One feels both blessedness and anxiety – but rather more anxiety!”

But not everyone was seduced by the Hungarian’s pianistic contortionisms. Clara Schumann, wife of composer Robert and a virtuoso in her own right, once dismissed him as a “smasher of pianos”, while the ultra-conservative Brahms felt that “the prodigy, the itinerant virtuoso, and the man of fashion ruined the composer Liszt before he even got started”.

No-one can ever be certain as to exactly what drove Liszt to ever-increasing heights of unparalleled virtuosity during these years, nor, of course, do we have any recordings or film to lend credence to the awestruck claims made by those who saw him. However, we do have a plaster cast of his hands that at least helps us to understand how he physically achieved his miracles.

His fingers were slender and long (although not unprecedentedly so), but their outstanding feature was the almost total lack of webbing between them, which allowed Liszt to accomplish huge stretches and finger-breaking intricacies with an ease closed to all but the most physically blessed of players.

If Liszt had so far inspired astonishment wherever he travelled, the biggest surprise came in 1848, when he promptly retired from the concert platform and accepted a full-time professional post in Weimar, where he now concentrated his attention on composing.

Up to this point, Liszt’s creative output had been fired by his virtuoso arsenal of pianistic pyrotechnics, but now he entered into a “middle” period during which the spectacular innovations of his youth were subsumed into a more sober and thoughtful musical style.

Among the musical highlights of this period are a series of 12 orchestral symphonic poems, the epic Piano Sonata in B minor, the Faust and Dante Symphonies, numerous keyboard transcriptions, and several large-scale choral pieces.

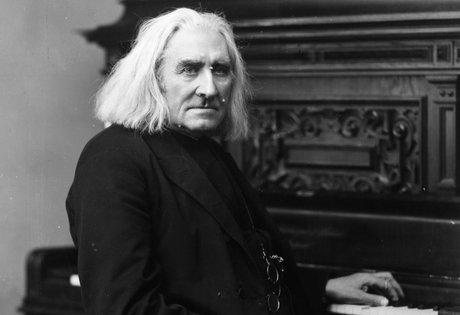

In 1861 Liszt moved to Rome, and four years later Pope Pius IX conferred on him the title of “Abbé”. Such was his latter-day devotion to the church that he eventually received an honorary canonry, although he was never ordained as a priest.

An apocryphal story tells that while he was preparing to enter the Holy Orders in Rome, Liszt was asked by the nuns after a service in the Sistine Chapel to play the piano. After he did so the nuns rushed at him and covered his face in kisses. Pope Pius therefore resolved that for the good of the clergy, he should be refused ordination.

Liszt’s later years were dominated by a series of inspired sacred compositions, many of which remain virtually unknown. Meanwhile, his piano music became more introspective and meditative in tone, much as Brahms’s music would a decade later.

He also spent much of his time commuting between Rome, Budapest and Weimar (his “vie trifurquée”) giving masterclasses (another of his innovations) and receiving visits from the greatest musical dignitaries of the age. Active to the end, even in 1886 (the year of his death) Liszt embarked on a tour that included his first visit to London in 40 years. He attended performances of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and Parsifal at Bayreuth less than a week before he died from dropsy complicated by pneumonia.

“Let us never put anybody on a parallel with Liszt, either as a pianist or a musician, and least of all as a man,” wrote the Russian virtuoso Anton Rubinstein, “for Liszt is more than all that – Liszt is an ideal!”

We shall never see his like again.