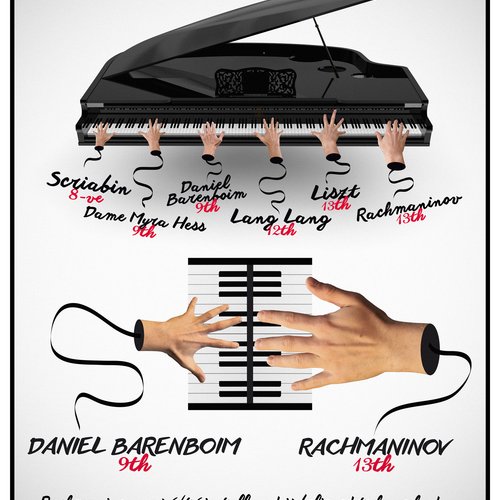

The 15 greatest pieces by Franz Liszt

20 September 2023, 17:40

Denis Matsuev performs F. Liszt's Totendanz

From finger-tangling piano études to full-bodied symphonic poems, here are the very best pieces of music by 19th-century Hungarian composer, Franz Liszt.

Listen to this article

One of the most prominent musical figures in 19th-century Europe, Franz Liszt was a prolific composer, conductor, and renowned virtuoso pianist.

At the height of his career, he was so admired that an erratic frenzy swept the continent on a level no other performer had even come close to experiencing.

Fans would travel the breadth of entire countries and further to follow Liszt on his tours. Fights would break out over his discarded personal effects. And it’s even said that Liszt had to take locks of hair from his pet dog and pass them off as his own, to preserve his own luscious mane and still meet the demand of his fervent fans...

Dubbed ‘Lisztomania’ in 1844, this flurry of fan behaviour even led to concertgoers wearing brooches and jewellery decorated with his portrait, in an early example of band merch.

Read more: Franz Liszt: discover the great Romantic composer’s life

Not least because of his swarming fanbase and 6’1” height, Liszt loomed large over the German music scene as an innovative and experimental performer and composer.

Over a six-decade career, he left behind a colossal amount of music – mostly piano, but also orchestral and vocal. Here are the 15 greatest pieces he ever wrote.

-

Mephisto Waltz No.1

Liszt wrote four Mephisto Waltzes, named for one of the most renowned demons in German folk literature (also known as Mephistopheles). Written in the years between 1859 and 1862, the first waltz is the most famous.

Subtitled ‘The Dance in the Village Inn’, it follows a part of Nikolaus Lenau’s Faust story, in which Mephistopheles and Faust join a village wedding party. The joyous festivities take a turn when the demon commandeers a violin and ekes out an ‘indescribably seductive’ melody. Faust, in turn, whisks away one of the village maidens, turning and twirling into the forest beyond. Ooh la la.

Franz Liszt: Mephisto Waltz No. 1 | Khatia Buniatishvili (Verbier 2011)

-

La Lugubre Gondola No.2

The dark and moody La Lugubre Gondola, which translates to The Black Gondola, is an important late work of Liszt’s. Whilst visiting his son-in-law and fellow composer, Richard Wagner, on Venice’s Grand Canal in late 1882, Liszt began composing the piece after having a premonition of Wagner’s death.

Lo and behold, on 13 February 1883, his eerie prediction came to pass. Liszt watched Wagner’s funeral gondola begin its journey through the aquatic city towards the rail station and Bayreuth, waves lapping at its sides. Sparse and contemplative, the introduction recalls Wagner’s Prelude to Tristan and Isolde, as the composer allows his grief, anger, and raw emotion to flow through his fingers, spilling out onto the keyboard.

Read more: Imposing organ rendition of ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ will get your heart racing

Liszt : La lugubre gondola S 200 n°2 (Alexandre Kantorow)

-

Three Concert Études, No.3: Un sospiro

If there’s one hallmark of Liszt’s piano music, it’s his ability to pack an unthinkable number of notes into just a few seconds. It takes a masterful pianist to translate the composer’s tumultuous musical cascade into the beautiful creation that lies beneath.

And what better performer to demonstrate than one of the all-time greats, Van Cliburn. Just have a listen to this...

Read more: Youngest ever Van Cliburn winner moved Marin Alsop to tears with this rapturous Rachmaninov

Un sospiro

-

Transcendental Études, No.4: Mazeppa

For much of the 1850s, Liszt must have been afflicted by the most terrible earworm – a tune so catchy that he had to use it in two different pieces of music for it to finally leave his head!

The first was published in 1852, the fourth of his Transcendental Études, titled ‘Mazeppa’. Its name comes from Ukrainian hero, Ivan Mazepa (single ‘p’), whose story has inspired an entire legacy of writers, poets, artists, playwrites and musicians.

As legend would have it, Mazepa was caught having an affair with the wife of a powerful man. As punishment, the scorned husband tied Mazepa, naked, to the back of a wild horse and set it loose to gallop the plains of Russia until it tired itself to death.

Liszt’s version for piano was inspired by Victor Hugo’s 1829 poem, full of galloping semi-quavers and a jagged waltzing melody that stumbles chaotically towards the piece’s finale.

Read more: The 16 best classical piano pieces of all time

Yunchan Lim 임윤찬 – LISZT – 12 Transcendental Etudes No. 4 (Mazeppa)

-

Les préludes

Liszt’s legacy is undeniably that of virtuoso pianist and piano composer – one of the world’s first ever bona fide rockstars. But his orchestral music is some of the finest to emerge from the Romantic era, igniting a decades-long feud with Brahms (known as the War of the Romantics), and sparking the invention of a whole new musical form.

Liszt is the father of the ‘symphonic poem’: a single movement piece of music, usually orchestral, which depicts a theme, scene or story through its music. Later popular with composers including Smetana, Sibelius, Dvořák and more, Liszt’s Les préludes is one of the first examples of the form.

Full of sweeping strings, plaintive wind passages and gutsy blasts from the brass section, this is Liszt at his orchestral finest.

Liszt: Les Préludes, symphonic poem No. 3, S.97

-

Piano Concerto No.1

Despite being one of the most prolific piano composers of his generation, Liszt only completed two concertos for the instrument. The first took him 26 years to write, beginning as a handful of themes in the 19-year-old composer’s sketchbook in 1830 before finally being published in 1856.

Consisting of four movements, the full performance lasts only around 20 minutes, but Liszt makes absolutely sure that every bar of music is well worth its salt. And when you’ve written something this sublime, it’s only right that you perform its premiere as Liszt did in 1855 under the baton of his good friend, Hector Berlioz.

Read more: The 20 best piano concertos of all time

Yuja Wang: Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major, S.124

-

Deux légendes

In 1863, Liszt wrote a pair of pieces for solo piano which are beyond compare in the remainder of his output. Based on miniature stories of two Catholic saints, St Francis of Assisi and St Francis of Paola, these Deux légendes provide a delicate insight into Liszt’s otherwise private religious and spiritual beliefs.

His relationship with the church ebbed and flowed over the course of his life, as he generated mistrust within sacred society with his flamboyant womanising lifestyle and obsessions with the macabre in his compositions. Yet he wrote a large number of sacred choral works, and for eight years in the 1860s he took up residence in the Vatican, later being known as Abbé Liszt.

This duo of pieces reveal an affection and sensitivity in Liszt for the Bible and its stories, as he uses the piano as a storytelling device to mimic the chirping of birds in the first piece and the aquatic rippling of the Mediterranean Sea in the second.

F. Liszt - 2 Légendes S.175 (Leonardo Pierdomenico)

-

Faust Symphony

Endlessly inspired by Germanic folk tales and demonic lore, it was only a matter of time before Liszt encountered Goethe’s most renowned tragic play, Faust. He was introduced to the work by Berlioz, who had written his own version of the man who sold his soul to the devil in 1852.

Liszt’s own brilliant contribution to the Faustian cultural repertoire came five years later in 1857, dedicated to Berlioz and premiered in Weimar, Germany, at the inauguration of the Goethe-Schiller Monument.

It’s no wonder this piece became a personal favourite of Leonard Bernstein’s, and his 1976 performance with the Boston Symphony Orchestra fittingly became the go-to recording for many. Just watch them in action below...

Read more: Maestro movie: plot, cast, release date and how to watch Bradley Cooper’s Bernstein biopic

A Faust Symphony

-

Mazeppa

Liszt’s second piece on the theme of Ivan Mazepa translates his 1852 piano piece into an orchestral masterwork, premiered two years later in April 1854. Although it uses the same main theme as its piano predecessor, Liszt’s orchestration is so refined it’s hard to believe that this wasn’t his original idea.

The symphonic poem uses a full orchestra, with the brass section taking the main theme for much of the piece as the galloping wind and string sections stir up clouds of dust that swirl behind the heels of Mazepa and his horse.

Liszt: Mazeppa, Symphonic Poem No. 6, S. 100

-

Liebesträume No.3

The third of Liszt’s 1850 Liebesträume trilogy is the composer at his most tranquil. Translating to ‘Dreams of Love’ in English, the piece is an adaptation of Ferdinand Freiligrath’s 1829 poem, ‘O love, as long as you can love!’

It has become one of the composer’s most beloved and enduring pieces, with its sweeping romantic theme and rolling passages that envelop you in a warm, musical embrace you’ll never want to end.

Read more: 10 of the best Romantic composers in classical music history

Lang Lang — Liszt's Liebestraum No. 3 on Steinway & Sons Spirio | r

-

Consolation No.3

Liszt’s six Consolations were originally composed between 1844 and 1849, but just one year later the composer revised the full set and replaced the third piece with the one best known today.

Chopin-esque in style, it’s said to be a tribute to the Polish composer who had died the year before. It was also one of the first pieces to make deliberate use of the ‘sostenuto’ pedal on the piano, which allows the pianist to sustain selected notes whilst leaving others unaffected, as Liszt re-transcribed the piece in 1883 after being sent a new grand piano by Steinway.

Read more: 10 best pieces of music by Frédéric Chopin

Liszt : Consolation no.3

-

Totentanz

Yet another example of Liszt’s all-encompassing obsession with death and themes of the grotesque, Totentanz (‘Dance of the Dead’) is a piece for solo piano and orchestra that opens with a raucous brass statement of the plainchant Dies irae, commonly used as a motif for death, which also appears in various other guises throughout the piece.

Liszt uses the piano as both soloist and percussive instrument in the single-movement piece, with staccato jabs that add chromatic melody to the timpani, and full-keyboard flourishes that demonstrate his flair for the dramatic, interspersed with calmer, more pensive solo piano sections.

Read more: Hans Zimmer hid this ominous medieval chant in his score to ‘The Lion King’

Liszt: Totentanz ∙ hr-Sinfonieorchester ∙ Bertrand Chamayou ∙ Jérémie Rhorer

-

Hungarian Rhapsody No.2

Popularised by Tom and Jerry and Bugs Bunny in the 1940s, Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No.2 is one of his most widely beloved pieces. Inspired by the folk music that he heard growing up in Hungary, Liszt wrote 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies between 1846 and 1885, as pianistic musings on the rich musical tapestry of his homeland.

Liszt uses his playful virtuosity to develop the theme, which begins as a dramatic and stately motif, later transforming into a sprightly iteration with a child-like innocence in the piano’s high register.

Read more: Virtuoso pianist perfectly syncs her playing with Tom and Jerry Cat Concerto scene

Jeneba Kanneh-Mason plays Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 | Classic FM’s Rising Stars

-

La Campanella (Grandes études de Paganini, No.3)

One of the most notoriously devilish pieces in the entire piano repertoire, Liszt’s dazzling La Campanella is demandingly virtuosic from the first note – and only grows in complexity over the following five minutes.

Nicknamed ‘The Little Bell’ after the persistent ringing notes in the high register, Liszt based the piece on the final movement of Paganini’s Violin Concerto No.2. Liszt takes a relatively simple theme and incorporates colossal jumps from high to low and back again at breakneck speed, finger-tangling trills, and overlapping melodies exchanged between the pianist’s left and right hands.

Read more: Niccolò Paganini was such a gifted violinist, people thought he sold his soul to the devil

Liszt - La Campanella Played on an LED Piano

-

Piano Sonata in B minor

Liszt achieved true perfection in 1853, when he completed his Piano Sonata in B minor. Dedicated to Robert Schumann, many have attempted to ascribe to it a meaning beyond the music, from yet another Faustian depiction to the story of the Garden of Eden, and even the suggestion that it could musical autobiography.

Unusually for a sonata, its movements are played back to back without pause, and at the time received a highly divisive response. Brahms, who had a long and tumultuous history with Liszt, is even said to have fallen asleep at its premiere, and one critic said that “anyone who has heard it and finds it beautiful is beyond help.”

Its technical difficulty also meant that it struggled to become a core part of the repertoire for some time, as even the most talented pianists of the time were wary of taking it on. Over time, however, Liszt’s masterwork found its audience, and today it is an absolute favourite of many pianists, music theorists, and classical music lovers across the globe.

Seong-jin Cho - Liszt : Piano Sonata in B Minor, S.178