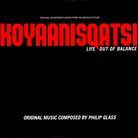

The Story Of Philip Glass

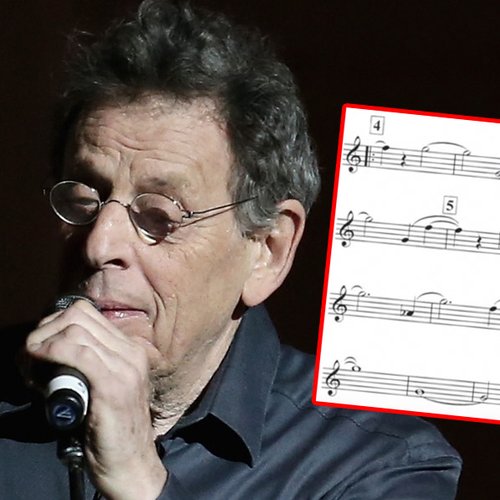

Philip Glass is one of the great creative originals of the modern age. He emerged in the 1960s at a time when contemporary classical music, spearheaded by those infamous “bad boys” Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez, had reached unparalleled levels of intellectual inscrutability.

Audiences of the time were regularly pounded into submission by scores that rejoiced in a complex network of “chance happenings”, or left bewildered by such onstage antics as deciding whether a grand piano was “hungry” or “thirsty” and dealing with it accordingly!

Just as the European mainstream had become temporarily hijacked by the avant-garde, a group of North American composers emerged whose declared intention was to go right back to basics.

Whole new soundworlds were created in which the smallest change was of the greatest significance – hence the term “minimalism”. Whereas repetition had become something of a dirty word in radical musical circles, such laid-back free-thinkers as Terry Riley, Steve Reich, John Adams and, most notably, Philip Glass positively thrived on it, creating mesmerising, mantra-like sequences of notes that would subtly get “out of phase” with one another.

Glass’s unconventional approach to music-making was nurtured in childhood. While most young kids growing up in 1940s Baltimore were out playing baseball, Glass spent hours being bombarded with music of all genres at his father’s radio repair shop.

At times, a number of sets might be switched on simultaneously creating an exhilarating blend of musical styles – imagine the liberating effect of that on a young creative mind!

Glass’s early exposure to classical music was no less unusual. His father ran an LP business on the side and would often bring home recordings of modern music with a view to getting his three children to explain why they weren’t selling.

As a result, Glass got to know the major works of Shostakovich, Bartók and Hindemith before he’d received a thorough grounding in the central classics.

This ultimately played havoc with his burgeoning sensitivities. Having been stimulated by the bracing eclecticism of his musical upbringing, the relative mundaneness of learning to play simple pieces on the violin, which he began to learn aged six, proved too much for young Philip.

Even his principal instrument, the flute, quickly lost its appeal. Disillusioned, Glass gave up any thought of making music his career and enrolled at Chicago University, aged just 15, majoring in mathematics and philosophy.

Just as his interest in music hit a low, Glass discovered the iconoclastic scores of his fellow countryman Charles Ives and the atonal musical landscapes of the Second Viennese School – Schoenberg, Berg and Webern.

He briefly dabbled in 12-tone techniques (or “serialism”) for a while, but it was the distinctly American music of Aaron Copland, William Schuman, Henry Cowell and Virgil Thomson that really fuelled his enthusiasm. Graduating from Chicago University in 1956, Glass packed his bags and headed for the Juilliard School in New York with the express aim of becoming a composer.

Although Glass was brimming over with first-rate ideas, his lack of formal training proved an obstacle. Lessons with such venerated figures as Darius Milhaud and Nadia Boulanger only seemed to make things worse as Glass struggled to find a coherent voice in the barren wilderness of academic tradition.

Then, quite by chance, he came into contact with the Indian composer Ravi Shankar. This was a turning point. Full of renewed energy and passion, Glass began researching the music of North Africa, India and the Himalayas, and returned to New York creatively revitalised and raring to go.

Remarkably, the composer hit the musical jackpot almost immediately with the formation of the Philip Glass Ensemble. This opened the floodgates on his creativity, giving him the chance to hone and refine his ideas with absolute freedom.

Following Music In Twelve Parts (1974), a four-hour epic which encapsulates his burgeoning genius for magical sonorities, the 39-year-old Glass created an international sensation with his first opera, Einstein On The Beach (1976). At last, modern audiences hungry for something more exciting than the traditional mainstream, but disillusioned by music that reacted consciously against it, found an entirely new world of beguiling innocence – one that tantalisingly bridged the gap between acceptance and anarchy.

Inspired by the unprecedented reaction to Einstein, Glass spent the next decade focusing on stage music. There were two follow-up operas – Satyagraha (1980) and Akhnaten (1983) – as well as a series of sparklingly original adaptations of the works of Irish writer and poet Samuel Beckett, which showcased the talents of Mabou Mines, a virtuoso group Glass had helped set up in the early 1970s.

By now he had achieved the kind of cult following normally associated with pop stars. His new-found celebrity status was confirmed when he was signed exclusively by record label CBS Masterworks (later Sony Classical), an accolade only previously awarded to two other giants of 20th-century music: Igor Stravinsky and Aaron Copland.

Glass’s first album for CBS, Glassworks, shifted 250,000 copies in its first year – something almost unheard of for a contemporary “classical” composer. Yet despite all the acclaim and material rewards, Glass kept his feet firmly on the ground, determined to remain true to his creative vision rather than composing music for the masses.

“I’m very pleased with it,” he quietly enthused. “The pieces seem to have an emotional quality that everyone responds to, and they also work very well as performance pieces.”

Never one to rest on his laurels, Glass felt ready, by the late 1980s, to tackle the kind of mainstream instrumental genres that had felt so unnatural during his student years.

Widely celebrated for the supreme concentration of his musical thought, he began expanding into the expressive opulence of the concerto and symphony. In 1987, he produced a Violin Concerto that at times appears to hark back to the 18th- and 19th-century traditions that Glass had so studiously avoided earlier in life.

“The search for the unique can lead to strange places,” Glass reasoned at the time. “Taboos – the things we’re not supposed to do – are often the more interesting.”

Glass’s terms of stylistic reference were broadened further still when he turned “crossover” with a pair of symphonies that synthesised classical and rock as though it was the most natural thing in the world. Inspired by the music of David Bowie and Brian Eno, Glass hit the headlines with his Low Symphony No.1 (1992) and “Heroes” Symphony No.4 (1996).

He later explained: “My approach was to treat the themes very much as if they were my own and allow their transformations to follow my own compositional bent when possible.”

Bowie gave the results his seal of approval with the immortal expression, emblazoned on countless T-shirts ever since: “Philip Glass rocks my ass”.

Glass continued his revitalisation of traditional classical genres with a series of five string quartets composed for the Kronos Quartet and a Third Symphony (1995) in which the terms of stylistic reference range from Haydn to Ravel.

Another feature of this period was a new interest in solo piano music, which expressed itself most notably, perhaps, in Metamorphosis (1988), an unusually melodious work that takes its name from a play based on a short story by Kafka.

Between 1993 and 1996, Glass produced an operatic triptych based on the work of the French writer and film-maker Jean Cocteau – Orphée, La belle Et La Bête and Les Enfants Terribles.

Up until this point, Glass had tended to compose music that left his listeners gently shaken rather than emotionally stirred. Yet following the death of his artist wife Candy Jernigan, aged just 39, Glass invested Orphée with unprecedented levels of expressive intensity.

This extraordinary depth of feeling also spills over into one of Glass’s most memorable works of the early millennium: his score for Stephen Daldry’s spellbinding movie The Hours (2002), which features the unforgettable miniature Dead Things.

To this day, Glass continues to produce music of extraordinary invention and vitality. In September 2005, the premieres of two new pieces were given: Waiting For The Barbarians, a theatre piece based on JM Coetzee’s novel, and an Eighth Symphony, whose instrumental dalliances and novelties one commentator likened to Bartók’s Concerto For Orchestra.

And last year, the choral work The Passion Of Ramakrishna, a film score for Paul Auster’s The Inner Life Of Martin Frost and a second volume of études for solo piano were all premiered.

The Essential Collection:

For the complete picture:

Einstein On The Beach (1976)

Glass Ensemble/Michael Riesman

The work that first brought Glass international acclaim, Einstein On The Beach is the first of his three “portrait” operas, which continued with Satyagraha in 1980 and, three years later, Akhnaten. This bristlingly inventive opera is scored for amplified ensemble and small chorus singing a text comprising numbers and solfège syllables (runs, scales, etc., that are sung to the same syllable or syllables).

Nonesuch 7559 79323-2

For expressive opulence:

Violin Concerto (1987)

Robert McDuffie (violin), Houston Symphony Orchestra/Christoph Eschenbach

“This piece explores what an orchestra can do for me,” Glass explained. “In it, I’m more interested in my own sound than in the capability of particular orchestral instruments. It is tailored to my musical needs.”

Telarc CD-80494

For crossover heaven:

Symphony No.1, Low (1992)

Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra/ Dennis Russell Davies

Based on Low by David Bowie and Brian Eno, the First Symphony borrows themes from three of the album’s tracks, combined with music of Glass’s own, and develops them into captivating “symphonic” movements.

Philips 438 1502

For raw intensity:

Mad Rush (1979)

Bruce Brubaker (piano)

Premiered by Glass on the organ for the Dalai Lama’s first public address in New York City, this most celebrated of his piano works builds imposingly towards a central climax before gradually fading away.

Arabesque Z6744