This exquisite Ella Fitzgerald song was based on a Debussy piano miniature

9 August 2021, 20:02

Dream-like Debussy makes a strikingly beautiful jazz standard, and especially when captured by the voice of one of the greatest singers of all-time.

When we say classical music meets jazz, the mind might turn to swinging, contrapuntal Bach in the style of Jacques Loussier. But here’s the proof that a gently lilting piano miniature can make a meandering jazz ballad as captivating as any.

The arrangement and lyrics were written by jazz trumpeter and composer Larry Clinton in 1938. Clinton took the melody from the 1890 piano piece Rêverie by the French composer Claude Debussy.

Read more: Jazz pianist finds ingenious way to correct audience clapping on the wrong beat

Debussy wrote the melody when he was in his late 20s. His dream-like Rêverie was one of his first solo piano works to make an impact. Even at this early stage in his career, there’s that signature sound, which became to be known as Impressionist music, or music that gently paints an image.

Clinton’s result, My Reverie, became an instant jazz hit.

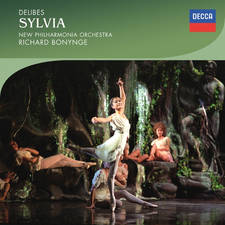

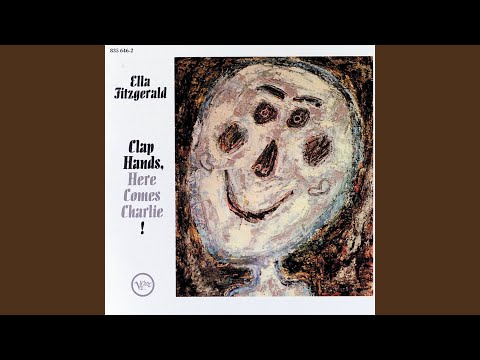

The great jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald recorded the song in 1961, with a jazz quartet. It was released that year on an album entitled Clap Hands, Here Comes Charlie!.

And with Fitzgerald’s alluring and effortless mezzo-soprano voice, Debussy’s lines radiate with a beguiling cool calm. Listen below.

My Reverie

Here’s star pianist Lang Lang with Debussy’s solo piano original:

Lang Lang — “Rêverie”, Claude Debussy

Jazz and impressionist music has a longer and more entangled history than you might initially think. New Orleans, Louisiana, was initially founded by French colonists, and it retained those strong trade, migration, and cultural ties to France.

Over the centuries, the city became a cultural melting pot. When jazz originated in the African American communities of New Orleans, in the late 19th and very early 20th centuries, it was at a time when the latest French musical trends were heard around the city, and influenced all those making music.

Later in the 20th century, the pianist Art Tatum drew anew on the harmonies of Debussy and Ravel, incorporating chord extensions such as elevenths and thirteenths in his improvisations.

At a time of deep racial segregation, the use of European musical traditions and techniques by Black players in an African American genre also made a quiet, yet powerful statement about the universality of art, music and expression.

Following on from Tatum, classically trained jazz pianist Bill Evans used French piano music in his harmony and chord voicings – as did the idiosyncratic and brilliant pianist Thelonious Monk when he improvised with Debussy-influenced whole-tone scales.

Music is full of these wonderful kinships across the continents and the centuries – making statements, and breaking down barriers because of it.