Why did Bernstein build West Side Story around 'The Devil's Interval'?

4 March 2019, 19:38 | Updated: 27 March 2019, 15:55

West Side Story is one of the world's most famous musicals. It's packed with great tunes and catchy rhythms, but there's an interval with a dark history at its heart.

Leonard Bernstein's West Side Story is based on and built around music's most unsettling interval, the ‘Devil's Interval’. Why would a composer do that?

First things first:

What is the Devil's Interval?

If you're a classical music buff, you'll know that ‘The Devil's Interval’ is a nickname for a musical interval called a tritone.

In a nutshell, a tritone is an augmented fourth interval (between C and F sharp). It's an interval between two notes separated by three whole tones.

For an in-depth explanation, have a look at our tritone analysis:

What is a tritone and why was it nicknamed the devil's interval?

Why is it called the Devil's interval?

The interval is so dissonant that it acquired the nickname diabolus in musica – the devil in music.

Instinctively, the human ear looks for harmony in music, and this jarring interval does the exact opposite of this. When used in music it frequently resolves itself by jumping to the nearby perfect fifth (one semi-tone away) for a musical resolution.

It seems a bit odd that Leonard Bernstein decided to use this ugly interval as one of his main motifs in West Side Story. But this was no accident: he knew exactly what he was doing.

Where do we hear the Devil's interval in West Side Story?

Frankly, it's everywhere. Blink and you'll miss a tritone.

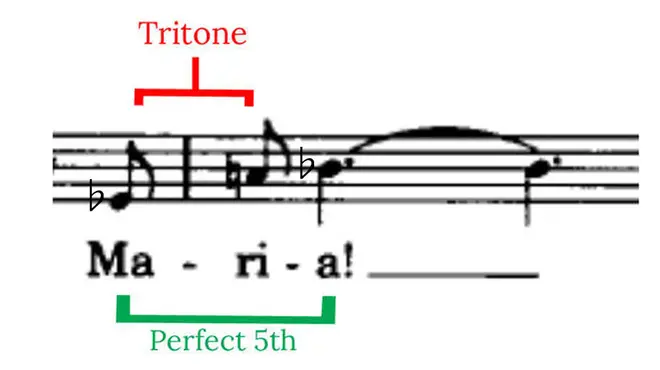

It forms the basis of some of the music's most iconic motifs. The most identifiable use of the tritone in West Side Story is in ‘Maria’. At 0.32 you'll hear the recognisable tritone jump:

West Side Story (3/10) Movie CLIP - Maria (1961) HD

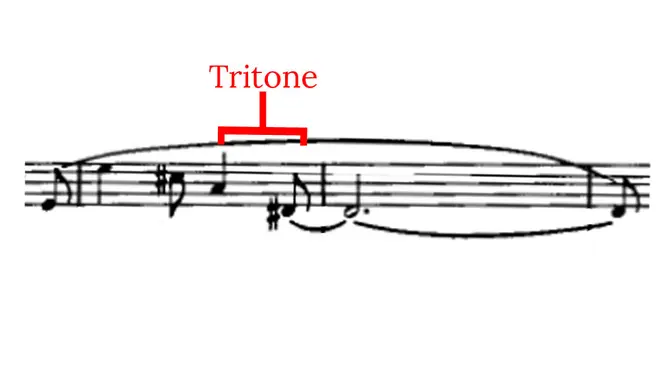

‘The Jets’ gang also have their own motif that pops up throughout the music. Unsurprisingly, the tritone takes centre stage.

Why does Bernstein use the tritone?

He uses this interval as the central idea that ties the whole score together.

It's worth noting at this point that Bernstein did something very different with West Side Story – he revolutionised the art of writing a musical. He wrote it as if it were an opera, with character motifs, musical foreboding and a musical narrative running through the score.

The tritone forms the basis of romantic songs, conflict songs, and the themes that intertwine the score together. It's also famously used in the unresolved ending of the musical, where two alternating tritones play out against each other.

Conductor Marin Alsop described the tritone as: “An interval that requires a resolution, and without resolution it just hangs there and makes you uncomfortable.”

In theory terms, it therefore serves two purposes:

1. It creates dissonance

2. When resolved, it creates one of the most satisfying harmonic resolutions.

This is Bernstein's tool to create a truly evocative score.

West Side Story - Cool (1961) HD

Why does it work so well?

Not only does Bernstein use this interval to tie the entire musical together, but the interval itself tells a story, and it adopts different meanings in different situations.

In different instances Bernstein will decide to either resolve the tritone or leave it unresolved. Leaving the tritone unresolved hints at violence and the danger around the corner, but resolving it hints at optimism and a different outcome for the characters. For example:

Resolved tritones: Tony's tritone in ‘Maria’

In ‘Maria’, the music couldn't be further away from the discordant sound that the tritone normally creates. This is because the tritone is only there for a moment before it moves up a semi-tone to create a perfect fifth interval.

Tony is filled with wonder having just met Maria, and his optimistic jump up from the tritone seems to brush away any unharmonic sound that comes with the tritone. The reality remains however, just like Tony's unfortunate end (spoiler), so the tritone is an integral part of the melody.

Even in the most optimistic and romantic of moments in the music, Bernstein keeps the tritone present as an ominous reminder of darker things to come.

Unresolved tritones: Jets motif and finale

The Jets motif doesn't resolve its tritone jump, it sits unresolved and does exactly what a tritone is known to do, create dissonance. From its first appearance, these unresolved tritones create the jarring harmony that mirrors the trouble to come in the plot.

At the end of the musical, after Tony's death, two tritone intervals sit next to each other, again with no resolution. It defines the plot's incompleteness: an unresolved interval, yearning to reach up to a musical resolution that it never quite gets. It's subtle, but packs a big punch.

Bernstein, you're the boss.