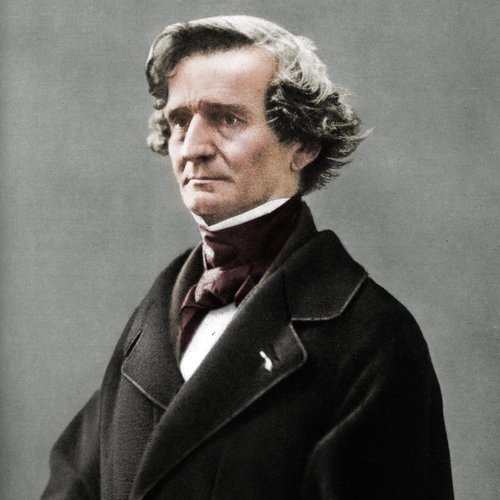

Discovering Hector Berlioz

Critics bayed for Hector Berlioz’s blood whenever his music was played but happily for the composer, today it’s their reputations and not his in the guillotine

Hector Berlioz was a one-off – a genius of such blinding vision that most of his contemporaries didn’t know what to make of him.

“His orchestration is so dirty that I have to wash my hands after turning over the pages of his scores,” Mendelssohn despaired.

Schumann moaned: “There is much in his music that is insufferable, but also a great deal that is extremely intelligent, and even full of genius.”

Distinguished critic Ernest Newman insisted: “A thing is never beautiful or ugly for Berlioz, it is either divine or horrible.”

The pianist and composer Ferdinand Hiller observed the same dichotomy in Berlioz’s face: “The glance, one moment flashing, actually burning, and the next moment dull, lustreless, almost dying – his mouth alternating between energy and withering contempt, between friendly smiling and scornful laughter!”

Ravel hailed Berlioz as “France’s greatest composer”, but with the caveat that he was “a musician of great genius and little talent” (Bizet had made the identical point in a letter of 1871), while Debussy merely dismissed him as “a monster”.

When Rossini was first shown the score of the Symphonie Fantastique, he reportedly exclaimed: “Mon Dieu, it’s lucky it’s not music!”

Indeed, with the honourable exception of Liszt – who masterminded a “Berlioz Week” in 1852 and arranged the Symphonie Fantastique for solo piano – only the Russians (Glinka, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Tchaikovsky) appear to have sung Berlioz’s praises unreservedly.

Incredibly, it wasn’t until the second half of the 20th century that the musical world finally woke up to the full extent of Berlioz’s blazing talent. Spurred on by Colin Davis – whose series of recordings have assumed legendary status – and musicologist David Cairns (author of the definitive biography), a very different view of the composer began to emerge.

The shattering contrasts and bracing unpredictability of Berlioz’s music took on a whole new meaning, making sublime those works that had previously been dismissed merely as “inspired ravings”.

One thing is indisputable: Berlioz was one of the all-time great orchestrators – indeed all modern concepts of scoring can be said to derive from his Grand Traité D’instrumentation Et D’orchestration Modernes (1843), which remains essential reading on the subject.

Supreme examples include the skin-tingling eruptions of brass, timpani and vast armies of voices that crown the Requiem’s Tuba Mirum, and the exquisite delicacy of that most celebrated of French song cycles, Les Nuits D’été.

Berlioz was also one of the most influential and charismatic of 19th-century conductors. In 1856, he summed up the art of the modern maestro in three sentences: “Performers should feel that he feels, comprehends and is moved. Then his emotion communicates itself to those whom he directs, his inner fire warms them, his electric glow animates them. He throws around them the vital irradiations of musical art.”

He was also a writer. Berlioz had a love-hate relationship with it, although he was one of the few great composers whose prose was as accomplished and insightful as his music.

“This self-perpetuating task poisons my life,” he agonised. “It can take eight or nine attempts before I am rid of an article... even when the subject excites or amuses me... the first draft is like a battlefield.”

But then Berlioz never did things by halves. Having started out as a medical student, he swapped disciplines mid-course and kick-started his formal music education at the Paris Conservatoire in 1826. He quickly established himself as a brilliantly inventive pupil with a series of highly original works climaxing with the Symphonie Fantastique (1830), a musical time bomb that had been fused and primed by his obsession with the Irish actress Harriet Smithson.

In a letter, Berlioz sounds like a man living on the very edge: “So many musical ideas are seething within me!... Now that I have broken free of the bonds of orthodoxy, I see huge vistas opening up before me, which academic stuffiness had previously forbidden me to explore... There are new things, many new things to be done, I feel it in every fibre of my being, and I shall achieve my aims, believe me, on my life.”

He and Smithson eventually married, but inevitably the reality failed to live up to his idealised image. Emotionally incompatible and constantly strained by Harriet’s bouts of illness, the couple were already living apart by the time of her death in 1854.

Meanwhile, the premiere of “their” symphony had gone down a storm – the March To The Scaffold fourth movement even had to be encored before the performance could continue with the finale. During harder times Berlioz would often recall this, his greatest triumph, as a source of emotional succour and support.

Berlioz again broke with convention with his second symphony, Harold In Italy (1834), which is uniquely scored for solo viola and orchestra. It was originally intended for Paganini, but the Italian pulled out as he felt the viola part wasn’t showy enough; on reflection, however, he was so impressed that he gave Berlioz 20,000 francs.

Berlioz’s next major work, 1837’s gargantuan Grande Messe Des Morts (or Requiem), left onlookers gasping at its unprecedented scale: “If I were threatened with the burning of all of my works except one,” Berlioz once reflected, “it is for the Requiem that I would ask for mercy.”

His Romeo And Juliet symphony of two years later has direct roots in its predecessors. Shakespeare’s “star-crossed lovers” had obsessed Berlioz ever since he’d seen Smithson playing Juliet in the 1820s, and Paganini’s payment enabled him to devote nine months to this extraordinary score, which fuses symphony and opera to devastating effect.

With Les Nuits D’été (1840-1) Berlioz established a new type of Romantic song cycle, which led directly to Gustav Mahler’s Lieder collections some half a century later. Then came another trailblazer, La Damnation De Faust (1845-6), a stunning adaptation of Goethe’s tale, which includes some passages of Berlioz’s own invention such as the hair-raising gallop to Hell; the author granted Faust a last-minute reprieve, whereas Berlioz has him consigned to the flames.

Then, only three years, later Berlioz wrote his earth-shattering Te Deum, which was premiered with 1000 performers, including a children’s chorus of 600.

Berlioz’s gift for the theatrical and monumental is illustrated by two Paris concerts he conducted during this period. The first, in 1844, required 1022 performers, including 36 double basses for Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, 24 French horns for Weber’s Der Freischütz Overture, and 25 harps for Rossini’s Prayer of Moses. Even this was dwarfed, however, by a spectacular in 1855 featuring a basic ensemble of 1200 players, plus extra choruses, brass ensembles, and five sub-conductors.

During his lifetime, few really understood what Berlioz was up to. Tired of perpetual criticism, he presented the central part of his enchanting 1850-4 oratorio L’enfance Du Christ as the work of one “Pierre Ducré” composed in “1679”. To his satisfaction, some critics were not only taken in but also suggested that Berlioz could actually learn a thing or two from “Monsieur Ducré”!

Increasingly troubled by a painful intestinal disorder, Berlioz began turning in on himself as never before. His five-hour epic opera The Trojans (1856-8) defied all his attempts to get a complete production staged, and although his last great work, the light-hearted opera Béatrice Et Bénédict (1860-2), was well received, it was too little, too late.

Despite some successful concert tours abroad, Berlioz died a disconsolate and lonely figure. An 1864 diary entry says it all: “My contempt for the folly and baseness of mankind, my hatred of its atrocious cruelty, have never been so intense.”

His Memoirs offer a poignant insight into the difficulties he faced in winning public acceptance: “If [certain people] were asked their opinion of the chord of D major (being warned beforehand that I had written it) they would declare with indignation: ‘What a detestable chord!’”

DEFINING MOMENT

Berlioz didn’t invent the idea of using a recurring theme (or idée fixe) to represent a specific thing, person or event, but he was the first to use the device to such devastating effect. Whereas most composers usually limit such “motifs” to a handful of notes, Berlioz extends his for a full 40 bars, most of it obsessed with the second half of the opening phrase [B]. Notice how he also throws in a “wobbly” in the second bar [A], which not only features shorter note values and a snappy dotted rhythm but also leaps about while the rest floats smoothly on.