Beethoven Piano Sonatas: a buyer's guide

Discover the best recordings of Beethoven's incredible piano sonatas on CD - click on the links to preview and buy them.

“Mozart is a garden, Schubert is a forest in light and shade, but Beethoven is a mountain range,” said the great Austrian pianist Artur Schnabel. And the terrain doesn’t come any more mountainous than Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas, with the massive Hammerklavier and the final three sonatas glistening peaks of achievement that few others have equalled, and none have surpassed.

It’s a proper mountain range too, with attractive foot hills like the three charming Op.2 sonatas, from the mid 1790s, though even here, as in the fiery opening movement of the No.1, there are intimations of the immense jagged outcrops to come.

Beethoven’s 32 is a cycle with a beginning, a middle and an end. It’s impossible to imagine what else he could have written after the magnificent, valedictory two-movement C minor sonata Opus 111, where the sonorities are so ravishing. Ravishing, Alfred Brendel suggests, because the left and right hands are so far apart, perhaps an act of desperation by Beethoven to try to create chords he could still hear, even distantly.

Equally, just because there is special substance to these final sonatas, this does not diminish the great middle- period ones like the Waldstein, and the gloriously turbulent Appassionata.

The good news for CD collectors is that all the complete sets available are excellent, without a single dud, and most are attractively priced. The bad news is that no single pianist holds the key to these great but often elusive works, or rather can convey every facet of these complex masterpieces. So one complete set won’t be enough, and even if you invest in a couple, you should still have some individual discs from great pianists who didn’t record the whole lot. Special readings like Rubinstein in Pathétique, Moonlight and Les Adieux (RCA) or Emil Gilels in any of the near complete cycle he recorded before his premature death in 1976. Similarly, the many live recordings of Sviatoslav Richter repay attention.

The good news for CD collectors is that all the complete sets available are excellent, without a single dud, and most are attractively priced. The bad news is that no single pianist holds the key to these great but often elusive works, or rather can convey every facet of these complex masterpieces. So one complete set won’t be enough, and even if you invest in a couple, you should still have some individual discs from great pianists who didn’t record the whole lot. Special readings like Rubinstein in Pathétique, Moonlight and Les Adieux (RCA) or Emil Gilels in any of the near complete cycle he recorded before his premature death in 1976. Similarly, the many live recordings of Sviatoslav Richter repay attention.

Now to the complete sets. It’s not just the fashionable pianists like Ashkenazy, Brendel or Barenboim who are illuminating here, but little known ones like Bernard Roberts or the top choice of many critics, Richard Goode. The claims of Jeno Jandó on Naxos are not to be overlooked, either.

Now to the complete sets. It’s not just the fashionable pianists like Ashkenazy, Brendel or Barenboim who are illuminating here, but little known ones like Bernard Roberts or the top choice of many critics, Richard Goode. The claims of Jeno Jandó on Naxos are not to be overlooked, either.

Paying full price for Goode isn’t recommended, when Stephen Kovacevich’s splendidly recorded digital cycle from 1991-2002 is available as an EMI box. This is our top recommendation. It should be augmented as follows: Daniel Barenboim was a young man when he recorded his first cycle, often, it’s said, playing them in the studio for the very first time. There is a buzz of excitement about these readings that I wouldn’t be without.

Paying full price for Goode isn’t recommended, when Stephen Kovacevich’s splendidly recorded digital cycle from 1991-2002 is available as an EMI box. This is our top recommendation. It should be augmented as follows: Daniel Barenboim was a young man when he recorded his first cycle, often, it’s said, playing them in the studio for the very first time. There is a buzz of excitement about these readings that I wouldn’t be without.

Two historical cycles are also must-haves. Artur Schnabel blazed a trail when recording them all in the 1930s. His set is one of the great milestones in the history of recorded sound, and can be purchased either as an EMI box, or separately, well transferred, on Naxos.

Two historical cycles are also must-haves. Artur Schnabel blazed a trail when recording them all in the 1930s. His set is one of the great milestones in the history of recorded sound, and can be purchased either as an EMI box, or separately, well transferred, on Naxos.

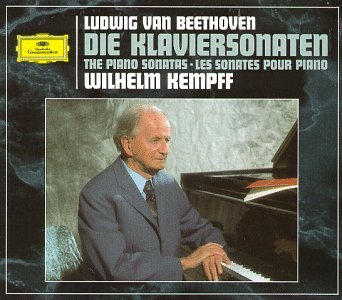

A special favourite is the earlier of Wilhelm Kempff’s two cycles, recorded between 1951 and 1956, when this great pianist was at the height of his powers. The sound is astonishingly good, and the performances full of wisdom.

A special favourite is the earlier of Wilhelm Kempff’s two cycles, recorded between 1951 and 1956, when this great pianist was at the height of his powers. The sound is astonishingly good, and the performances full of wisdom.