Discovering The Great Composers - Béla Bartók

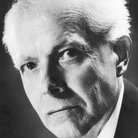

A reluctant revolutionary who tried to adapt the natural rhythms and phrasing of ancient Hungarian folksongs to mainstream classical music, or a subversive reactionary who all but brought the Western tradition to its knees? Whatever your opinion, there has never been another composer like Béla Bartók

“If the reader were so rash as to purchase any of Béla Bartók’s compositions, he would find that they each and all consist of unmeaning bunches of notes, apparently representing the composer promenading the keyboard in his boots. Some can be played better with the elbows, others with the flat of the hand. None require fingers to perform nor ears to listen to.”

This damning report, which appeared in the very first edition of The Musical Quarterly in 1915, sums up the kind of resistance to his work that Bartók endured throughout his lifetime.

Yet for Bartók composing was as imperative as it had been for Bach, Beethoven and Brahms.

“I cannot conceive of music that expresses absolutely nothing,” he once wrote. “My own idea is the brotherhood of peoples, brotherhood despite all wars and conflicts. I try – to the best of my ability – to serve this idea in my music”.

Perhaps the world simply wasn’t ready for him. As late as 1964 Colin Wilson reflected in his popular novel Brandy Of The Damned: “He [Bartók] not only never wears his heart on his sleeve; he seems to have deposited it in some bank vault”.

But surely this is to miss the point. As Aaron Copland put it: “The literary world does not expect TS Eliot to emote with the accents of Victor Hugo or Walter Scott. Why, then, should Bartók be expected to sing with the voice of Schumann or Tchaikovsky?”

Bartók’s parents were teachers and amateur musicians. According to his mother Paula: “When he was four years old he could play with one finger on the piano the melodies of all the folk songs he knew; he knew 40 in all...”

This signalled a childhood that saw young Béla actively composing by the age of nine. He gave his first public piano recital just two years later. Had he accepted the offer of a scholarship to the Vienna Conservatoire in 1898 things may have turned out differently.

But the passionately patriotic 17-year-old opted instead for the Budapest Royal Academy of Music. Such was his astonishing rate of progress that by the time he graduated in 1903 he was confidently composing in the Liszt/Richard Strauss orchestral mould, and was seemingly aware of his musical destiny: “For my own part, I shall have one objective: the good of Hungary and the Hungarian nation.”

Bartók formed a musical alliance with Zoltán Kodály and set about collecting Hungarian folksongs. This extraordinary repository of musical ideas formed the bedrock of Bartók’s fast-developing musical style.

He later explained that “the extremes of variation, which is so characteristic of our folk music, is at the same time the expression of my own nature”.

Meanwhile, Bartók found himself increasingly in demand as both pianist and composer. In 1905 he caused a sensation with a Budapest performance of Liszt’s fiendishly difficult Totentanz, the following year he toured Spain and Portugal with the brilliant young violinist Ferenc Vecsey, and in 1909 he conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in a performance of the Scherzo from his Second Suite.

The next two years also saw him prepare critical editions of Beethoven and Mozart piano sonatas. Meanwhile he accepted a post at the Budapest Academy in 1907 and, although he loathed teaching, he stuck it out for more than a quarter of a century.

On a happier note, in November 1909 he married his pupil Márta Ziegler, who the following year bore them a son, Béla Jnr. They divorced in 1923, soon after which Bartók married another pupil, Ditta Pásztory.

Things were by now moving very quickly. Bartók’s immersion in the folk material he had collected from Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Transylvania, Turkey and North Africa was now combined with the harmonic and textural revolutions wrought by Debussy to produce a First String Quartet (premiered 1910), whose uncompromising introspection and tonal unpredictability set the tone for the rest of his output.

It is hardly a coincidence that just as he was setting out on a defiant new creative path, he embraced the writings of Nietzsche and became a religious sceptic: “The existence of the universe does not require the hypothesis of God,” declared the firebrand composer.

“Why don’t we simply say that we can’t explain the origin of its existence, and leave it at that?”

Like many other composers struggling to find their creative feet during the first two decades of the last century, Bartók produced music in a bewildering array of styles.

One minute he might obsess about the motoric nature of rhythm (Allegro Barbaro For Piano, 1911), the next galvanise his audience with emotionally superheated outbursts of instrumental and vocal colour (the opera Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, 1911).

He delighted in approachable little miniatures, such as the popular Romanian Folkdances of 1915, yet his trailblazing spirit led him to create a balletic scorcher, The Miraculous Mandarin (1919), which propels the folksong inheritance towards its outer limits.

Although Bartók obscured any strong feeling of key, he shrank from abandoning tonality altogether. But despite the occasional tonal life-raft, many listeners are still left flailing in deep waters.

No wonder the ultra-conservative Korngold could make nothing of Bartók’s First Piano Concerto in 1927: “The piano becomes a machine, the orchestra a machine workshop, and all this in the service of a brutal, crudely materialistic noise, and all signifying a kind of Hungarian-Russian-Bolshevik machine art”.

Bartók was now a cause célèbre, an uncompromising modernist whose work was appearing in print (thanks to a contract with Universal Edition) almost as fast as he could compose it. Yet it wasn’t until the late 1920s to ’30s that all the conflicting elements fused together to produce a steady stream of indisputable masterpieces.

These range from the breathtaking rhythmic propulsion and ear-tweaking sonorities of the Sonata For Two Pianos And Percussion (1937) to the post-Romantic luxuriance of the Second Violin Concerto, completed the following year; from the skin-creeping atmospherics of the Music For Strings, Percussion And Celeste (1936) to the nostalgic approachability of the Divertimento For String Orchestra (1939).

Fearing the capitulation of Hungary to Germany – he referred to the Nazis as “bandits and assassins” and forbade broadcasts of his music in Germany and Italy – Bartók became increasingly aware that he would not be able to stay in his homeland.

The thought of leaving depressed him and his heart sank at the thought of returning to teaching – he had finally left his job at the Budapest Academy in 1934. But following the nerve-jangling introspection of his Sixth String Quartet (1939), Bartók escaped the horrors of war for New York.

Bartók initially found that the pain of separation from friends and family precluded any serious composing. Then a commission from the conductor Serge Koussevitzky opened the floodgates once more, releasing the warm emotional waters of the Concerto For Orchestra, Third Piano Concerto and the incomplete Viola Concerto.

Even the critics seemed happy: “The music of Bartók ennobles all who hear it,” read one report. The composer had one last surprise up his sleeve, however, with his uncompromising Sonata For Solo Violin (1944), written for Yehudi Menuhin.

Bartók died of polycythaemia on September 26, 1945 a broken man, bringing full circle a prediction he had made to his mother in 1905: “I prophesy that this spiritual loneliness is to be my destiny”. In 1988, Béla Jnr arranged for his father’s remains to be transferred from Woo Cemetery in New York to Budapest, satisfying his fervent wish, stated just months before his death: “I would like to go home – forever”.