Steve Reich Rolls On

Steve Reich tells Classic FM about his debt to John Coltrane, why his new pieces can be so hard to write and why he can’t stop innovating.

It hardly seems plausible that Steve Reich has reached his three-score-years-and-ten. Minimalism always seemed such a young man’s game, but it’s now some 40 years since this musical fraternity, of which Reich was a leading light, became the latest underground movement to wow a New York scene that’s always been thirsty for fresh sounds.

Reich – and his composer compadre Philip Glass – were urgently looking for a route away from the academic 12-tone composition, or serialism, they had been obliged to study at music college. All around them the air was thick with the sounds of modern jazz, rock’n’roll and what is now labelled “World Music”. Reich realised he would have to follow a path more in tune with the breadth of his musical interests, and created a music that renewed tonality and mesmerised listeners through the mantra-like qualities of repeating pulses.

“I was studying frankly impenetrable serial composition by day, and going to John Coltrane gigs at night,” Reich recalls, the punch of his speech patterns sounding noticeably akin to the rhythms of his music.

“Composers around me doing serial pieces usually couldn’t hear what they were writing, but Coltrane was standing up on the bandstand and just playing. I realised I needed to form an ensemble to play my own music and that 12-tone music was like a mock funeral, leading to a bunch of assumptions about harmony that simply weren’t true.”

Since those formative Road To Damascus years, minimalism has moved from the underground to enter the US’s mainstream. Reich added up in his mind a music that fused his love of Coltrane and Miles Davis with repeating patterns, and formed the now legendary Steve Reich Ensemble to play it.

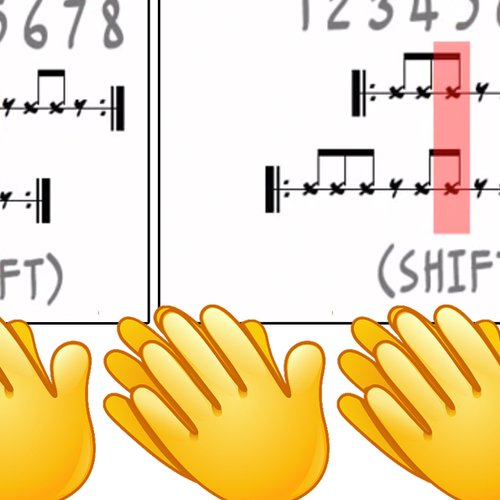

Those trademark recurring patterns evolved from his appreciation of bebop’s momentous grooves and from his experiments with looping speech patterns on tape. Reich recognised that repeating a snippet of speech over and over created intriguingly lithe melodic contours, and soon similar melodies were permeating his instrumental music, as heard in his 1988 classic Different Trains.

The Nonesuch label celebrates Reich’s graduation from young lion to old tiger with the release of two recent works, You Are (Variations) and Cello Counterpoint. The former is a choral and ensemble piece with aphoristic texts about the creative process and the development of human consciousness.

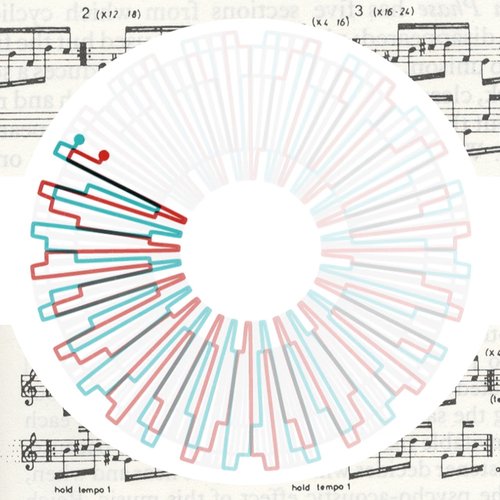

During Cello Counterpoint, Reich has the cellist play real-time counterpoint against a bank of recorded cellos, an idea he instigated back in 1982 with Vermont Counterpoint, written for flautist Ransom Wilson.

“I found Cello Counterpoint a very difficult work,” Reich reflects, “so when the time came to start You Are (Variations) I decided, look, I’m going to take a great deal of pleasure doing something very familiar and see where it leads.

“The opening begins with interlocking mallet-instrument patterns, but about halfway through the first movement all four pianos join in and the harmony suddenly shifts to more complex chords. So, start with something you know how to do, and you may end up doing something you never knew you knew how to do!”

Reich’s approach to vocal music has a freshly baked quality that junks classical protocol. In his earlier seminal ensemble works such as Drumming and Music For 18 Musicians, Reich treated vocalists in the same way as regular acoustic instruments: they vocalised his melodic shapes without words.

But what effect does using words have on his vocal writing?

“It’s exactly the same vocal style,” Reich says. “The ‘doopy-doops’ in Drumming came out of scat singing in jazz, but when there’s a text I’m thinking Ella Fitzgerald meets [English countertenor] Alfred Deller.

“The opening text in this piece - ‘You are wherever your thoughts are’ - by an 18th-century mystic, is also a wonderful description of how to listen to music – wherever the music goes you follow, and this is about how the mind can wander and explore. But the second movement, ‘I place the Eternal before me’, from the Psalms, is a place to meditate and give listeners space. The harmonies are the basic chords you find in Classical music and rock’n’roll, in contrast to the more adventurous harmonies in the opening.”

You Are (Variations) ends with a text by Wittgenstein reflecting on the fact that scientific exploration can never end; it’s just that ideas and technologies need to catch up with advancing frontiers. Reich senses his own craft evolving in the same way.

“One thing Schoenberg overlooked [when he said traditional Western tonality had nowhere else to go and should be replaced by a new system] was that the longer you hold a particular harmony the more ambiguous the notes within it become, a phenomenon that’s all over my own music. So I reckon the possibilities for composers – like the frontiers of science – are endless.”