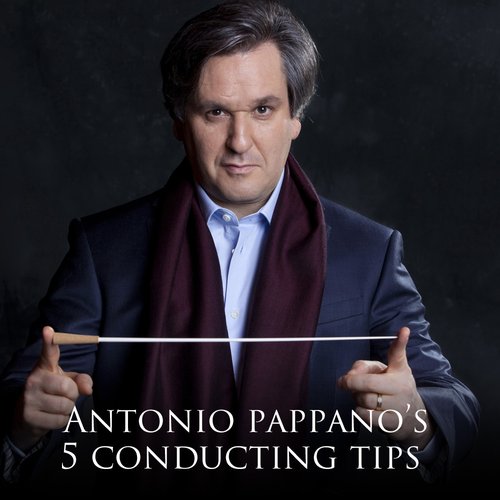

‘We shouldn’t be ashamed of charging money for our concerts’ – Pappano on how classical music can survive COVID

2 July 2020, 14:44 | Updated: 3 July 2020, 10:03

As the UK government supports industries out of the coronavirus pandemic, leaders in opera are asking how their art can return to full strength.

Four leaders in the opera world have met virtually to discuss the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the UK’s proud opera heritage.

In a meeting chaired by the Royal Philharmonic Society’s CEO James Murphy, Royal Opera House director of music Antonio Pappano, star soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn, tenor Trystan Llŷr Griffiths, and head of costume at Scottish Opera Lorna Price discussed (watch below) the most urgent challenges facing live music.

“These are extraordinary times for us all, and particularly for the performing arts,” Murphy says. “Right now, you’re likely hearing a tsunami of animated advocacy from all sorts of voices, each speaking out for music whilst – in lockdown – it can hardly speak for itself.

“Our intention with these conversations is to cut through some of the current noise and try to give music-lovers a candid, sincere and human impression of how music-makers are faring through all this.”

Read more: Simon Rattle urges, reduce 3-metre woodwind distancing in orchestras >

The RPS Conversation - Opera (part 1)

Murphy’s discussion with Pappano and others gives a glimpse into what happened the moment live opera suddenly came to a halt, while assessing what needs to be done to help the classical music industry return to its pre-lockdown strength.

The key, for now, is for artists to stop being afraid of charging money for their concerts – which are almost exclusively still being presented online in the UK, out of necessity – while making sure the government is accountable for the science and support it provides to allow the arts to return at the same rate as other industries, while lockdown eases.

Read more: ‘Every musician I know is facing bankruptcy’, say classical artists >

“I was in the middle of a run of Beethoven’s Fidelio”

Like other big events in history, we who have experienced coronavirus lockdown will now be able to recall what we were doing when the profound restrictions were applied to our lives.

“I was in the middle of a run of Beethoven’s opera Fidelio – a new production – and there was a lot of hype around it, especially around the fact we were doing a live cinema performance,” Pappano says. “It was really a tough blow, I must say.”

Soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and tenor Trystan Llŷr Griffiths add, they were both starring in big productions and had to suddenly stop working and fly home.

“We were in the middle of a really busy season,” head of costume at Scottish Opera, Lorna Price says. “We’d just finished John Adams’ Nixon in China and we had Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream which was about to go into the theatre. We were going to do a dress rehearsal but even that didn’t happen in the end.”

“We found ourselves making lots of scrubs for the NHS”

Price and her team pivoted quickly to frontline work for the coronavirus crisis.

“We have a transferrable skill,” she explains. “We can make 18th-century costumes so of course we can make glorified pyjamas. Our tailor Ali Currie had seen a Facebook Page called ‘For the love of scrubs’ and I have a lot of contract workers who I saw signing up for this group. I got in contact with the company and they said they could let us in a few days a week.

“We made 820 sets of scrubs in five weeks for the NHS.”

Griffiths found himself singing every week in solidarity with the NHS, just after people took to the streets on Thursday nights to ‘Clap for our Carers’.

The RPS Conversation - Opera (part 2)

“These are desperate times for freelance contract staff”

It’s important to remember the crisis in music isn’t limited to the performers we see on stage.

Head of costume, Price says: “It’s desperate. A lot of the people in my industry are freelance contract staff. My whole team have been very lucky because Scottish Opera have been very supportive and they have managed to keep people on furlough, so even the contract and casual staff are being paid through the furlough system.

“But when that finishes what are those people going to do? It’s not like they can go out and find other work because there isn’t any other work... Technicians are quite a hardy bunch – when there isn’t work, they’ll get a bar job, a waitressing job. But at the moment they can’t even do that.”

“We have to feed our hungry audience”

Pappano highlights the new approaches to music-making in lockdown that he’s experienced, especially in terms of education, which organisations turned to in COVID to keep the passions of audiences missing the arts fed.

“You can study and learn things,” the conductor says, “but we realise that a different culture of work has developed. What we’re doing right now, I don’t remember doing before – I’m doing these clips for the Royal Opera House website that involve informative analysis of scenes and virtual duets with people.

“I’m trying to do everything with an educational aspect to it, we have to feed our audience who are very hungry.

“The people who support us love music, so we need to give them something. But at some point we’ve got to get back to what we do.”

Trailer: Watch Live from Covent Garden 13 June

“We shouldn’t be ashamed of charging money for concerts”

Musicians need to pay the bills like all of us. “Streaming, even with a nominal payment from the audience, is a new initiative [for many]. Will some of this stay when we get back to normal? Maybe,” Pappano says.

“When I see the numbers of people who watch broadcasts of opera – 700,000 people [in some cases] – it’s a lot, and it’s quite amazing.”

Streaming has largely been offered for free to audiences. On that, Llwellyn says: “I guess I feel that it is important to make this art, and to be generous with the way we offer our art around us, but at the same time we have mortgages, rent, children, elderly parents. When I got back from Germany I was slapped with a very big bill to do repairs to my house, and I didn’t have the money to pay it but I had to do it, so there is a big hole in my bank account I wasn’t expecting.

“What I would like to see, going forward, between streaming things for free and tantalising people with the ideas and the music and the art, is to sell it in some sort of way. I would like to see some of our streaming actually creating revenue, not just for singers but for the backstage team and the techies as well. Why aren’t we selling it more?”

Pappano agrees. “That’s what we’re doing with our concerts [Live from Covent Garden],” he says. We gave one free concert and then for the second and third programme we charged a nominal fee of £4.99…

“I think it is a bargain, and we shouldn’t be ashamed of charging money for our concerts. I think one of things we have to be careful of creating is a society which expects everything for free.”

One drawback to streaming is, of course, the lack of audience feedback. “When you’re doing streaming it’s just you, the artists and cameras, and I tell you it feels quite lonely,” Pappano confirms.

Howard Goodall’s ‘Never to Forget’ – Trailer

“The government needs to give us a lifeline”

Unfortunately, revenue from online creativity can’t be the whole story. A lot of conversation around the survival of live music, arts and concert halls and theatres at the moment revolves around government funding.

“At the moment it doesn’t look great economically [for] getting back to normality,” Pappano says. “And all normality will be based on whether the government comes through and gives us a lifeline so we can survive through the period through December.

“If we can get far there might be a chance we can get back to normality.”

Read more: Oliver Dowden faces criticism for ‘lip service’ over real funding for the arts >

“I hope we get the science right”

“I hope we get the science right, because it seems very contradictory to other information from other places,” Pappano says. “So singing is actually the stumbling-block. That’s what we’re prohibited from doing. I think there was a statement saying, ‘fine, musicals can come back, but no singing’. How is that possible?”

Audiences have to be distanced too, of course, and the government’s latest guidance is 1 metre+, which means a mask must be warn and other measures taken.

Read more: Opera stars say ‘break quarantine’, citing packed flights but near-empty concert halls >

And there’s the worry of a second peak in the pandemic.

Two musicians play 'Amazing Grace' in an abandoned church

Pappano adds: “We’ve got to be seen to be preparing for a second outbreak of COVID-19 which is a serious business, but you can also be very serious about how you’re trying to tackle the problem. Just saying ‘we can’t tackle the problem’ is unacceptable to me.”

“It’s not just the government but also [what the] the British people [do], and if we get a second spike,” Llewellyn chimes in. “We still haven’t reached flu season.”

She adds: “I was speaking to a casting director the other day and they were concerned that these two things are still potentially ahead of us. I was asking about a production I’m meant to be starting at the end of January, and they made the point that so much depends on whether we’re legally allowed to gather and rehearse, and that is completely out of our hands.

“It’s about the British people doing what the government says, and sticking with the rules to try to avoid this second spike. But we’ve also got to be realistic about how desperately people want to get back to their normality.”

The RPS Conversation is a new series, available on Royal Philharmonic Society’s YouTube Channel and website, exploring leading musicians’s personal experiences of the coronavirus pandemic. Visit royalphilharmonicsociety.org.uk to find out more.