Who was Jacqueline du Pré, the legendary cellist who brought the Elgar Cello Concerto to the masses?

24 January 2025, 16:13 | Updated: 24 January 2025, 16:33

Although she died in 1987, the image of cellist Jacqueline du Pré still resonates as one of the most recognised and beloved musicians of all time.

Listen to this article

Jacqueline du Pré, who would have turned 80 years old this weekend, is recognised as one of the greatest cellists of all time.

It is difficult to state in words how significant her contribution to the world was. In her relatively short career, she worked with some of the era's greatest musicians and left behind many legendary recordings. Despite her career being cut short in her late 20s, her impact on the musical world has stood the test of time.

She was born into a musical, middle-class English family in Oxford on 26 January 1945. At age four, Jackie was struck by the sound of a cello playing on the radio, telling her mother, “I want to make that sound”.

After this revelation, her mother Iris – who was a concert pianist herself – arranged for Jacqueline to take lessons in cello and piano, acting as her first teacher. She later moved on to lessons with the celebrated cellist William Pleeth (whom she nicknamed her ‘cello-daddy’) at the age of 10.

Read more: What’s the history of Elgar’s Cello Concerto – the work with a disastrous premiere?

Jacqueline du Pré: A unique and enduring legend

“The cello was Jackie’s being, her life, her heart and soul,” Jacqueline’s sister, Hilary Finzi, told Classic FM.

“She loved playing. Mum never introduced her to conventional practising, knowing it would destroy her vibrant instinct. When Jackie, aged 14, met Rostropovich for the first time, he suggested she might like to warm up by playing a scale. ‘What’s that?’ she asked.”

She progressed rapidly, winning the Guilhermina award – Britain’s most prestigious cello award – at 11 and making her Wigmore Hall debut at 16.

Her 1965 performance of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in America brought her international fame and shortly afterwards she appeared as a soloist with the best orchestras worldwide. In the same year she made a recording of the piece with Sir John Barbirolli and the LSO, which is the stuff of legends, setting the benchmark for the work.

Despite already reaching this level, in 1966 she chose to study with the famed Mstislav Rostropovich in Paris, who declared Jacqueline ‘the only cellist of the younger generation that could equal and overtake [his] own achievement’.

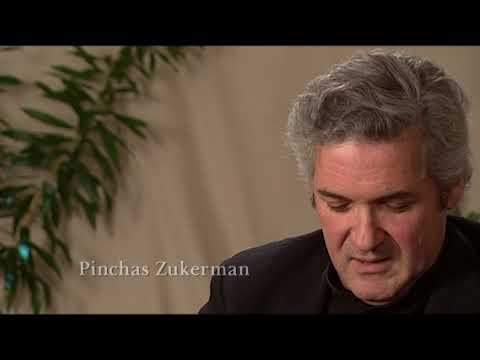

Du Pré embarked on a glittering international career, performing and recording with fellow young musical stars such as Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman, Zubin Mehta and Daniel Barenboim, whom she married in 1967. Barenboim and du Pré were regarded as a ‘golden couple’ in the music industry during the late 1960s and early 1970s, producing numerous recordings of the highest quality.

Speaking to Classic FM, Jacqueline’s brother Piers Du Pré recalled: “At 19 years old, Mum, Dad and I flew to Tel Aviv on Wednesday 14 June 1967, the day before Jackie was to marry Daniel by Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall.

“That evening, Jackie and Daniel were giving a concert in Tel Aviv. Zubin Mehta was conducting. Having been used to UK concerts, imagine my total astonishment when the audience was on its feet, applauding, and flocking to the stage reaching out and calling to them. And that was as the final bars were still being played.”

Read more: Ballet based on life of British cellist Jacqueline du Pré coming to Royal Opera House

Du Pré’s style of playing is characterised by its huge emotional range and intensity. Her interpretation of Dvořák’s fiery Cello Concerto manages to simultaneously capture a yearning quality combined with an earthy, full-blooded and quintessentially Czech sound.

One remarkable live performance in 1968 at the Royal Albert Hall – thankfully preserved on YouTube – took place just days after Soviet tanks rolled into Prague, making the occasion even more significant. Du Pré rose to the occasion and it is impossible not to feel the power of her performance, 60 years on.

She was one of those rare artists who managed to truly inhabit the music she was playing, no matter the style, era or genre.

Jacqueline du Pré: a gift beyond words

Tragedy struck in 1971, as Du Pré’s playing declined as she began to lose sensitivity in her fingers and other parts of her body. She was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in October 1973.

During a tour of North America, she was met with criticism from the public, a worrying sign of the disease’s hold over her. During rehearsals with the New York Philharmonic and Leonard Bernstein, she had problems judging the weight of her bow and even struggled to open the case of her cello.

Tragically, she was only 28 when her playing career came to an end, but she continued, while she was able, to teach and give masterclasses.

“Perhaps it isn’t quite so bad for you, Miss du Pré, as you’ve achieved so much,” remarked a journalist after she stopped playing.

She replied, “I haven’t achieved anything. I could always just do it.”

Her death in October 1987 at the age of 42 was marked by an outpouring of grief worldwide. She was one of the very few classical artists who achieved household name status and the tragedy of her career, cut short at the height of her powers, continues to inspire and affect people today.

Perlman, Mehta, Barenboim and du Pré Having Fun During a Rehearsal

In 1998 the film based on du Pré’s life called Hilary and Jackie was released. It was a critical and box office success, but received criticism from Jacqueline’s closest friends and colleagues including Daniel Barenboim and fellow cellists Mstislav Rostropovich and Julian Lloyd Webber. Her life has also inspired a Ballet, The Cellist, based on her life and an opera by Luna Pearl Woolf.

She was decorated with numerous awards during her life and was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in the 1976 New Year Honours. At the 1977 BRIT Awards, she won the award for the best classical soloist album of the past 25 years for Elgar’s Cello Concerto.

In the words of her sister, Hilary, “Jackie did not analyse or study the music she played but went into the hearts of the composers through their music. Now, when I listen to the few master classes she gave after she had to stop playing, I am astonished at how much thought and interpretation she displayed in words.”