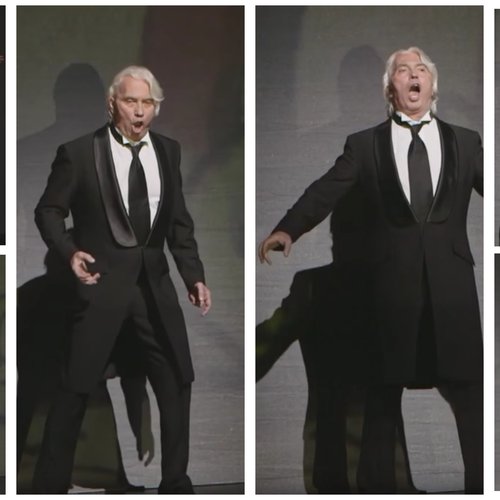

Dmitri Hvorostovsky And Bryn Terfel: Battle Of The Baritones

No one who saw the final of the 1989 Cardiff Singer of the World competition could forget it. After a titanic battle between two world-class baritones, one of them scooped the top prize and the other took the Lieder prize.

The respective winners were, of course, Dmitri Hvorostovsky and Bryn Terfel. Their paths have, since Cardiff, largely diverged. Hvorostovsky has glided his silken way to the top of the Verdi ladder, while Terfel has hit a Wagnerian jackpot as Wotan in the Royal Opera House’s Die Walküre.

“I think Bryn is finding his place as one of today’s greatest Wagnerian baritones,” Hvorostovsky says. “It’s ironic that at the same time he was singing Wotan at Covent Garden this year, I was doing Rigoletto there, something that went a good way towards fulfilling my own dream of becoming one of the top Verdi baritones.”

Their first encounter all those years ago was probably as unforgettable for them as for the audience.

“We were both very green!” Hvorostovsky smiles. “I was slightly older than Bryn and I’d already won two major competitions, in Russia and France. By the time I got to Cardiff I was unbelievably arrogant and ignorant and thought I was experienced. And I never doubted that I was going to win – until a few minutes before I had to sing in the final, when I heard Bryn singing full out and saw the audience’s reaction.

“I thought, ‘Oh no! Well, I might get third place…’ The trouble was that I didn’t have a tail suit, so I’d borrowed money to buy myself one against the money I expected I’d get for winning first prize! “At that moment, I started to doubt myself for the first time: Bryn had such a luxurious, beautiful voice and phrased so beautifully that it almost knocked me over. But I hoped that Verdi was going to win for me, because I sang Rodrigo’s death scene from Don Carlos, which had become my trademark a couple of years before. I really did hope it would save me.”

It did.

Did he and Terfel get along?

“I could hardly get around in English then, and Bryn spoke with a strong Welsh accent, so I couldn’t understand anything he said except for ‘Hi’ and ‘Bye’!”

Since then, though, they’ve worked happily together in Mozart, with Terfel singing Figaro to Hvorostovsky’s Count in The Marriage Of Figaro in Salzburg in 1995 – “Bryn ate me alive and spat me out!” the Siberia-born Hvorostovsky laughs.

These days, his repertoire centres on Verdi. He’ll be singing Renato in Un Ballo in Maschera at Covent Garden in November and December; next year he’ll be taking on the title role in Simon Boccanegra for the first time. What attracts him so strongly to Verdi?

“Most of his operas are based on classic plays or stories by Hugo, Shakespeare and so on, and I’ve always felt deeply affected by the heroism and romanticism of the literature.

“It’s an amazing combination of story, libretto and music. And the music is genius. Everything Verdi wrote for the baritone voice is beautiful, comfortable and perfect. Verdi’s cantilena is the best in the world. So I can enjoy myself vocally, while the characters are always challenging and complex,” Hvorostovsky says.

Another role he will be bringing to Covent Garden this season is the title role in Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin. To many, Hvorostovsky looks the perfect anti-hero Onegin – handsome, cool, enigmatic – but it will only be the second time he’s sung it at the ROH, and the first since 1993.

“I’m sure it will be different,” he says, “because I’ve changed. Onegin won’t be the young, green boy any more – he’ll be not just an older Onegin, but a more sour Onegin. Cynical, maybe. Or perhaps less cynical! It depends…”

And while Terfel’s output has included West End hits, Hvorostovsky branched out into a crossover field of his own recently when he toured Russia with a programme of war songs, performing for veterans of the Second World War, and televised to an audience of some 100 million.

“Soon I’m going to do another tour with some classic Soviet-era songs,” he says. “I don’t feel it’s compromising to do this repertoire, as it’s a little like ‘classic pop’ – and I’ve achieved a level of popularity that I could never have achieved in opera alone.’”

But he seems unlikely to go head-to-head with Terfel again. “I quit singing Don Giovanni,” he says. “I want to stick with the roles I identify with. Someday I will sing Wolfram [in Tannhäuser], but my Wagnerian singing may end there. I could never sing Wotan – it’s not my cup of tea. I am Bryn’s admirer and I can remain so, at a safe distance!”