On Air Now

Relaxing Evenings with Zeb Soanes 7pm - 10pm

8 May 2024, 12:01

Toxic levels of lead in two locks of hair belonging to Beethoven could shed light on the cause of the composer’s lifelong health struggles.

In 1802, Ludwig van Beethoven wrote a devastating letter to his brothers, Carl and Johann in what is now known as the ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’. The 31-year-old composer expressed his despair at losing his hearing, confessing it had driven him to such misery that he had considered ending his life.

Only art had saved him, he wrote, saying he could not leave the earth until he had exhausted all that he felt he had left to write.

He also left his two brothers with a plea: that his illness and death be studied by doctors, “so that as far as possible at least the world may become reconciled with me after my death”.

Now, as medical science develops in leaps and bounds, Beethoven’s wish may be one step closer to coming true.

A new analysis of locks of the composer’s hair reveals eyebrow-raising levels of lead, mercury and arsenic that scientists say could begin to explain Beethoven’s gastrointestinal problems, and possibly even his hearing loss.

Read more: Ultra-realistic image of Beethoven created by visual artist using composer’s own life mask

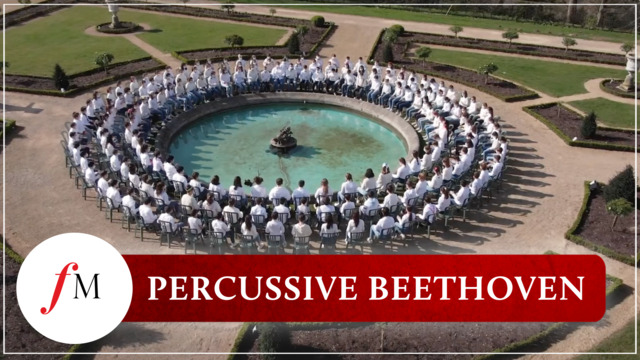

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony as a body percussion epic played by hundreds of schoolchildren

Of eight locks in existence said to belong to Beethoven, only five are now believed to have been cut from the head of the composer.

One of the eight, known as the ‘Hiller’ or ‘Guevara’ lock, was previously analysed and found to contain high levels of lead. But in 2023, a study found that this lock of hair had actually belonged to a woman, not to Beethoven.

The same study identified that five of the locks of hair shared identical genetic information and were therefore certainly from one person – or possibly a pair of identical twins.

One of these locks of hair had been sold for £35,000 at a Sotheby’s auction in 2019, and can be directly traced back to the pianist Anton Halm. Beethoven himself cut and hand-delivered this lock to Halm, after the pianist had been tricked by a fellow musician with a lock of hair cut from a goat.

With this historical evidence and anecdote, the scientists said that there was “compelling evidence” for these five locks to be the real deal.

Read more: A lock of Beethoven’s hair has just been sold at auction – and it went for a whopping £35,000

The study that identified five authentic locks of hair also found that Beethoven had a genetic predisposition to developing liver disease, and was infected with Hepatitis B at least in the final years of his life – a scientific development Classic FM presenter and Beethoven expert John Suchet described as “the most exciting news to come out about Beethoven’s health” in 20 years.

More recently, in July 2023, skull fragments thought to belong to Beethoven were returned to Vienna for study, but are yet to be authenticated.

Read more: Scientific analysis of Beethoven’s DNA reveals he had Hepatitis B and high risk of liver disease

This new study, published in the scholarly journal Clinical Chemistry, examined two of the authentic Beethoven locks and found that both had very high levels of lead concentration, up to almost 100 times what is considered average.

The study also found elevated levels of both arsenic and mercury, around 13 and 4 times higher than usual, respectively.

Levels of lead concentration this high wouldn’t be enough to have killed the composer, the study says, but are “commonly associated with gastrointestinal and renal ailments and decreased hearing”.

As for how Beethoven managed to consume quite so much toxic heavy metal, the study points to “plumbed wine, dietary factors, and medical treatments”.

Beethoven was famously partial to a drink or few. He was known to drink a bottle a day or more, believing it was good for his health, and was even spoon-fed gulps of the stuff on his deathbed. His last words – “Pity, pity – too late!” – were uttered as he discovered a crate of 12 bottles had arrived from his publisher, and he had no time left to drink them.

Cheaper wines at the time were often sweetened using lead sugar, and the metal was commonly used at various stages of the wine fermentation process, from the kettles it was stored in to the corks used to seal the bottles.

What’s more, Beethoven saw many doctors from his early 20s to his death at 56, seeking a cure to his tummy woes and hearing loss. Prescriptions ranged from electric currents applied directly to the ear, to bathing in tepid water from the River Danube.

At one point, he was taking 75 medicines simultaneously – several of which, it is reasonable to presume, contained lead.

Read more: The pianist who dared to challenge Beethoven to a musical duel in Vienna – and his fate…

Beethoven Symphony No 9 Flashmob in Nuremberg, Germany.

In the light of these new scientific discoveries, Beethoven expert John Suchet told Classic FM: “The high levels of lead will undoubtedly have exacerbated Beethoven’s perennial problems of poor digestion, diarrhoea, liver disease and, we now know, Hepatitis B.

“But I would be cautious about attributing Beethoven’s deafness to lead poisoning. He first complained of problems with his hearing in a letter of June 1801 when he was 30 years of age. It is highly unlikely he had dangerously high levels of lead in his blood at this early age.

“Also his copious drinking of cheap contaminated wine was something that developed much later in life. So the cause of his deafness remains a mystery. One day though, given the advances in science, we will certainly know.”